TABU

Mavericks und heisse Eisen

26.1. —

17.3.2002

Taboos are traditionally seen as violations against the values or basic norms of society. Every cultural group follows its own rules and norms of behaviour for social coexistence. Behavioural forms that guarantee familiar forms of communication within one group of people can be perceived as transgressions by another. If such rules of conduct are ambiguous they can not only permit greater freedom, but also present opportunity for further taboos to erupt. For the media, the taboo is a welcome phenomenon because it sees in it the potential for scandals. In the case of tabooing, however, roles are defined by the relationship between ‘the tabooed’, the ‘tabooer’ and the public who acts as arbitrator in ascertaining the existence or non-existence of the taboo. See: Peter Zimmermann and Sabine Schaschl, Skandal: Kunst, Wien: Springer, 2000.

A society’s list of taboos reveals its state of mind, its freedom or standards: the more taboos in a society, the more rigid and moral are its rules for coexistence. Too few taboos, on the other hand, could lead to social transgressions, which the events of September 11 in the US demon-strated to us with unequivocal vehemence. By destroying the World Trade Center the terrorists broke not only the taboo of killing, but especially also that of killing the innocent. They struck at the pulsating heart of a world power no one had ever dared to challenge so far. What made their transgression worse was the choice of arms, more vicious than any known, turning planes into weapons, kerosene and human beings into ammunition. They had found their justification under the pretext of Jihad, of Holy War, and therewith touched one of the most enduring taboos of all: untoward legitimation through religion. Osama bin Laden’s followers, in disregarding the West’s belief in religious tolerance, inadvertently brought to attention the necessity of taboos for safe-guarding social codes.

The word “taboo” comes from the Polynesian islands of Tonga and describes a prohibition or restriction that could mean touching, saying certain things or acting in a certain way. Freud in Totem and Taboo (1912—1913) says: “The taboo restrictions are different from religious or moral prohibitions. They are not traced to a commandment of a god, but really they themselves impose their own prohibitions; they are differentiated moral prohibitions by failing to be included in a system which declares abstinences in general to be necessary and gives reasons for this necessity. The taboo prohibitions lack all justification and are of unknown origin. Though incomprehensible to us they are taken as a matter of course by those who are under their dominance” (Sigmund Freud, Totem und Tabu, Frankfurt/Main, 1991). In search of “similarities in the souls of savages and neurotics,” Freud not only attracted the attention of his admirers but also his sharpest critics amongst the cultural anthropologists.

Encountering the phenomenon of the taboo with the means of contemporary art is unusual, particularly because the taboo — with the exception of the still effective historical ‘evergreens’ — is recognised as such only in retrospect, usually following a scandal. Before this backdrop, discourses that discern the condition of a society through potential rifts emerge as even more revealing. The exhibition Taboo — Mavericks and hot iron explores precisely these ‘areas’ to detect the presence of personal, private taboos or day to day taboos. It is essential, however, to immerse oneself in the personal, private and everyday stories that are the subject of many of the selected works. The state of tensionbetween so-called mavericks and their potential for being stamped with hot iron describes, as it were, those states between ‘unscathed’ and ‘branded’ which define taboos.

Text by Sabine Schaschl

Richard Billingham (born in 1970 in Birmingham, lives in Stourbridge, UK) became famous through the portraits of his family that allow insights into a life of impoverishment and extreme alcohol and cigarette consumption.

The line of distinction between the private and the public is drawn at the doorstep of his parent’s flat, which the artist never shows. Speaking about his photographs he says, “Neither I nor they (my parents and brother) are shocked by the directness of the photographs in “Ray’s a Laugh” because we’re well enough acquainted with having to live with poverty. After all there are millions of other people in Britain living similarly...” (Richard Billingham: a short, by no means ex haustive, glossary, Michael Tarantino in exh. cat. Richard Billingham).

A lot in his works ‘draws’ a fine taboo zone without ever allowing the taboo to become effective. Although addiction, poverty or crossing the threshold between private and public are surely themes with a strong potential for taboo, they can be kept within bounds under the ‘cover’ of art because the field of art contains more free zones for the unspeakable than so-called ‘normal life’ does. In Billingham’s video Play Station of 1999, the focus is consistently on his brother’s hands manipulating the console with uncanny speed. His fingernails, broken and bitten to the skin, the game’s musical sounds in the background and the fragments of speech all tell their own story about the subject’s social environment. The incessant movement of playing hands conveys a sense of pain and on watching longer one inevitably thinks of an addiction that is not much spoken of — the addiction to games.

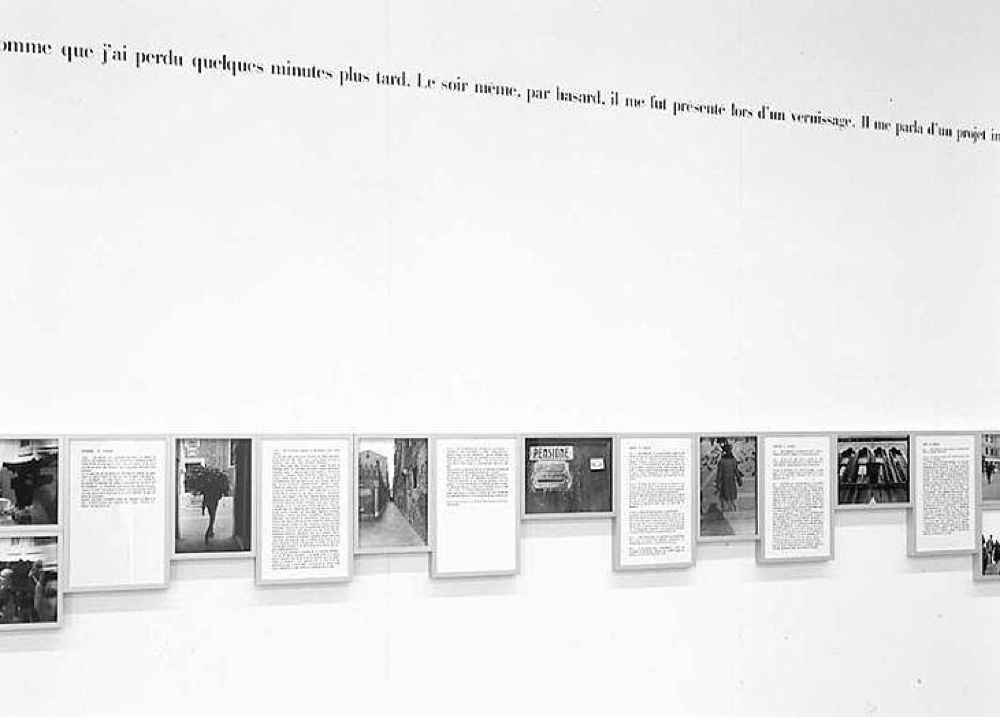

In 1979, when Sophie Calle (born in 1953 in Paris, lives in Paris) returned to Paris from her travels, her sense of loneliness prompted her to follow strangers around the streets with her camera. Around the end of January 1980, she met a man at a party whom she had lost sight of during one of her pursuits.

The few things she did know about him were his name and his imminent visit to Venice. The artist decided to follow him there. Once in Venice, she called hundreds of hotels till she found the pension the stranger had moved into. She followed his movements as far as possible, capturing on her camera his environment, the sights that interested him and if she had the opportunity to, even photographed him. She expected nothing of him, least of all sexual escapades — she did not even find him particularly attractive. She spoke about him to people who had crossed his path and found out about his interest in antiques as well as several other details about his life. Her artistic investigation was neither aimed at reversals of gender roles in an observer-observed-relationship, nor at emphasising an ostensibly female gaze. It was much more her own feelings and those of others that Sophie Calle explored during her pursuits. We learn very little about “Henry B.”, the followed; all we get to see is his back. While public surveillance is accepted by society as a necessity today, personal observation is much more a taboo than it was prior to the “Political Correctness Movement”. On looking more closely it seems absurd that what is considered a taboo individually is tolerated when given a place in society.

His subtle but at the same time profound questioning of the supposedly established makes the art of Adam Chodzko (born in 1965 in London, lives in London) stand out. In 1995, he advertised for his work The God Look-Alike Contest in international papers for people who believed they looked like God, requesting them to send him their photographs. This simple request brought all sorts of things to light that would not have been so easily possible in a verbal discussion. Women and men, couples of different colours and nationalities responded and their mere belief that they resembled God shattered several rules and representations of God upheld by various religions. Cf. The two series ofGod Look-Alike Contest: one advertised in Great Britain and one internationally. Also see Adam Chodzko, catatogue, Gallery II, University of Bradford, Nothern Gallery of Contemporary Art and Viewpoint Gallery, Salford, 1999. On seeing this series the imaginary male, white God of the western Catholic and Protestant Church is relativised as rapidly as perhaps his coloured counterpart in the respective cultures. On the other hand, the series can also be read as a literal equivalent of: “Man was made in the image of God.” But when asked to imagine God, most cultures stubbornly insist on an image determined by socio-cultural factors. ( I would like to remind the readers of the countless negative reactions to works of the women artists who replaced the body of a male God with that of a naked female body. (E.g. Bettina Rheims))

Adam Chodzko’s artistic method is like a ‘background activity’ that makes the actions and reactions of people especially possible and even activates them. At the same time, his works evolve around themes that suggest something unspeakable, a taboo. The manner in which feelings related to ‘death’ are subtly dealt with in his video Limbo Land, or the themes ‘superstition’ and ‘extrasensory powers’ in his most recent video Plan for a Spell substantiate this.

In the case of food, several rules of behaviour stand in contradiction to each other. “Eat whatever is on the table!” is diametrically opposed to the noblesse oblige of leaving a morsel on the plate. Well meant advice of mothers to daughters, “The way to a man’s heart is through his palate” is fortunately applicable to both genders today because preparing meals is no longer just the task of women.

For the exhibition, the Basel based performance group GABI explores taboos related to food. Founded in the year 1998, they describe themselves as a loose group that reconstitutes itself from performance to performance and has no steady number of performers. The group’s constant members are Martin Blum, Lena Eriksson, Martina Gmür, Haimo Ganz, Samy Kramer, Irene Maag, Muda Mathis, Gabriele Rérat, Judith Spiess, Chen Tan, Franziska and Günther Wüsten.

Work in relation to wage is also the theme of the performances of San Keller (born in 1971 in Bern, lives in Zurich). In his perfomance San Keller sleeps at your place of work, the artist will offer his services in the form of sleep to employers, employees and freelancers who can engage San Keller as a sleeper at their place of work. The artist will use his own sleeping equipment for the job and the wage will be adjustable to the income of the employer. Keller addresses in this project the extremely complicated evaluation of art by arguing with economic ‘usefulness’. The delicate theme he touches here comes from the art market itself that, as Simon Wood has said previously, forgets the artist in its system of value appreciation. In contrast to other fields, the art market distinguishes itself through extreme exploitation. Nowhere else are statements like, “Well, artists (and of course curators) just happen to earn less,” simply accepted without much ado. Speaking about salary in the art world is still a taboo that is very far from belonging to the past.

The Dutch artist Renée Kool (born in 1961 in Amsterdam, lives in Amsterdam and Strasbourg) loves sabotaging systems — not for the sake of sabotage but much rather to expose the absurd and questionable. On the occasion of the Manifesta 1 (Rotterdam 1996), the curators of the exhibition offered her a ‘transparent space’ without themselves ever having seen it. The fact that this building was supposed to be transparent was reason enough for them to offer it to her (a woman artist!). It appeared as if ‘putting on display’ and ‘woman’ were seen as related terms. These were the events that led to the work au-delà.

Based on the Manifesta experience, the artist erected a new and altered version of the work at the Kunsthaus Baselland in which she incorporated factors specific to the new site. Two of the videos that are fixed elements supposedly belonged to the material taped by surveillance cameras, now on the increase in correspondence to global insecurity. One of them has caught a young woman looking at herself in the mirror, doing a rehearsal, as it were, for ‘being seen’. The second one shows a man in his underpants conducting an orchestra from a window. With the best concert hall at his feet, he seems oblivious of the fact that he could be observed. While the young woman who was caught accidentally is examined as an object of desire, the scene with the conductor usually provokes laughter. Renée Kool’s work speaks volumes about society’s double standards. Surprisingly enough, without cringing even once, we pay for a greater sense of security with our freedom and intimacy. Even the surveillance of our everyday lives and its visual image has its visual receivers — a fact that we easily forget.

The works of Zilla Leutenegger (born in 1968 in Zurich, lives in Zurich) are as she herself puts it, like windows that she sometimes opens to let others look at her romantic world.

The language of Romanticism serves her to bridge the gap between herself and the recipient. The Man in the Moon in her video installation is actually a woman in the moon who has learnt to piss like a man. This occupation of territory is not just humorous, for it also references the achievements of eminist theoreticians. For the artist, emancipation today means bringing out each gender’s individual qualities. So when Leutenegger conquers the moon with male conduct, she is not interested in emulating specific poses and gestures but much rather their models: How is intellectual affinity expressed in our mass culture? What examples of it exist and how are they conditioned? Films repeatedly show us fathers and sons pissing together to underline their bond. But we as recipients can sense this taboo zone of role distribution, which is not very old.

The setting of the video installation My first Car, which Zilla Leutenegger is showing in addition to The Man in the Moon is likewise a moon landscape. This time, however, a car from which throbbing sounds of music emanate drives around a moon crater in an endless loop. Each time the car comes closer to the viewer the music also becomes louder to fade into the background along with the car. This senseless cruising is related to idle diversion or killing time, characteristic of not just the youth. Both these traits are severely rejected by Western economy and its work-oriented society, but could possibly be accepted behaviour of everyday life in other societies.

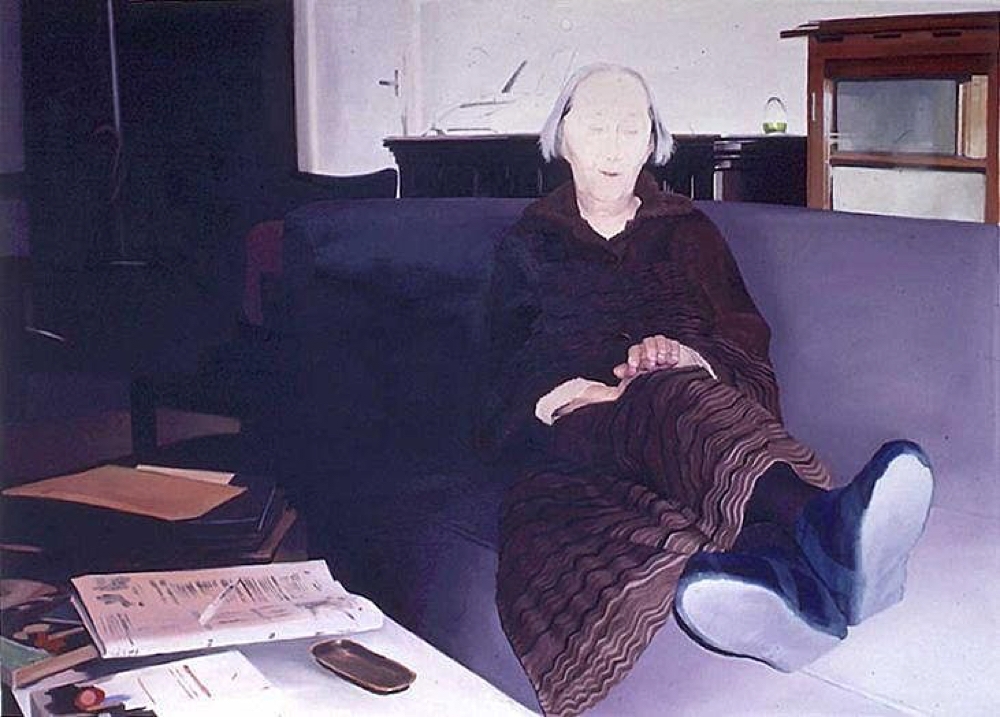

Janice McNab (born in 1964 in Aberfeldy, Scottland, lives in Edinburgh) shares Javier Téllez’s interest in questioning society’s relationship to disease. In her second last series (1999—2001), the artist worked with people suffering from the effects of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS), also called the disease of the 20th century. Caused by various common substances present in our environment, it can lead to so many allergies and physical reactions that the patients have to live in almost complete isolation.

During one of her trips to Mexico, the artist tried to meet MCS patients. Already a week before her visit, she had to stop using perfumed shampoo or make-up, wash her clothes in sodium bicarbonates and even stop painting during the entire period. She captured some moments of her encounters on photographs which she later translated into paintings in her studio that so far comprise the MCS and industrial workers series. In the latter, the artist concentrates on a group of workers in the “Greenock factory” and in the Motorola manufacturing plant in Scotland, who have reason to believe that the cocktails of chemicals they come in contact with at their places of work cause cancer, miscarriages and infertility. The case is still pending in court. The theme of the artist’s large paintings is not only isolation and inner emigration of the victims, but above all the absurdity of the debates that put health issues at work versus retention of the job itself (cf. exh. cat. Janice McNab, doggerfisher, Edinburgh 2001 and Tramway, Glasgow 2002). The real issue is economy versus individual health — a taboo subject, which is unpleasant and preferably suppressed.

Ever since his childhood, the artist Javier Téllez (born in 1969 in Valencia, Venezuela, lives in New York) has been involved with psychiatric institutions and their inmates. His parents, who are both psychiatrists, taught him how to deal with mental disability in everyday life and this is now the source of many of his works.

For Téllez, museology and psychiatric clinics employ the same parameters of classification for differentiating between the ‘normal’ and the ‘pathological’. In his own words, “The processes of selection and marginalisation constitute their main modus operandi, be it employed within the framework of art history or the study of human behaviour. The therapeutic dogma common to both disciplines is behind the fact that both doctors and exhibition curators employ the same verb to define their practice: to curate the body, artistic or physiological.” (Javier Téllez, Of a hospital within a Museum, in exh. cat. La extraccion de la piedra de la locura, Miseo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, 1996, p. 40).

The curation (lat. curare) of once the body and then of art, link the two areas that Téllez unites in his work. In the video installation Bounced, which is on exhibit, the close-up of a mental patient becomes the projection surface and target of tennis balls shot at regular intervals. Surprisingly, the visualisation of an act considered taboo — namely hitting or hurting another person — usually triggered mirthful reactions. (I would like to thank Serge Ziegler for his observations.) In Pendulum, however, in which the recipient himself is called upon to “throw” a projected face, the social taboo becomes active and the threshold is hardly ever crossed. This leads to the assumption that viewing an act is not as subject to taboos as one’s own actions are.

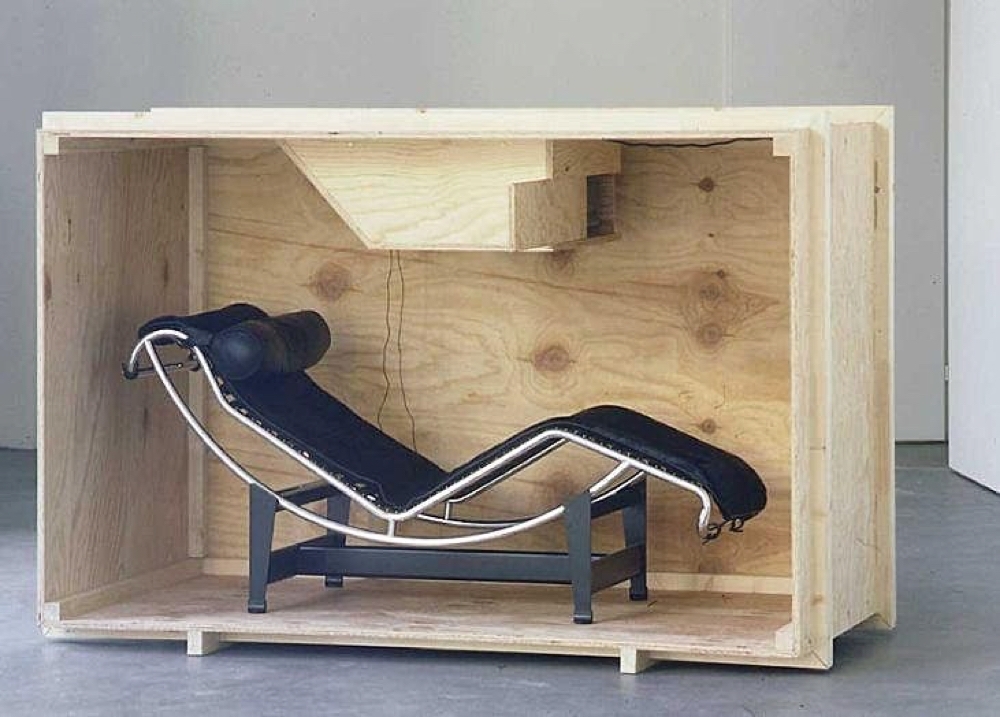

In his work LC4/R-Machine Javier Telléz invites the visitor to relax in a comfortable Corbusier reclining chair to the softly played Golbergvariations of J.S. Bach that perfects the mood. The chair, however, is tightly fit into a wooden box and whoever reclines in it unexpectedly finds himself in direct eye contact with a mentally disabled person smiling at him encouragingly from the monitor. Telléz provokes a ‘real’ confrontation here and unobtrusively forces the viewer to re-evaluate his relationship to the disabled.

Objects and stories linked to them The story that the teaset by Martin Walde (born in 1957 in Innsbruck, lives in Vienna) is based on began in 1994 when a 19th century teaset was rediscovered in the attic of his parent’s house. Astonishingly enough, nobody seemed to rejoice in the discovery, for the secret of this find brought to light an unpleasant incident after which it was never used again. It appeared as though this occurrence had undergone an “objectification” with unpleasant connotations. Martin Walde, whose work is primarily concerned with contextualised processes, used the object’s aura of taboo and presented it on an over-sized table along with a text offering it for exchange. Blue light immerses the object into another level of consciousness, making it reminiscent of the crazy tea party in Alice in Wonderland. To ensure the exchange he demands an object with an equivalent past. In a way it is the stories associated with the object, which become ineffective when in the hands of a “neutral” owner, that Walde exchanges. A positive form of forgetting is practiced through the act of changing hands: setting free, giving away, letting go and forgetting as activities relevant to life. Since the artist first exhibited the teaset in 1996, he has received innumerable offers and would have nearly made the deal once had it not been for the horrendous taxes on the accident-damaged car. In Walde’s work, individual feelings and actions expressed through art become inter-woven with the proposals of art. In the words of Harald Uhr, “his artwork is about creating an order that involves us as active beings”, (Harald Uhr, Vier künstlerische Positionen als Botenstoffe mentaler Ressourcen, in: Kat. Transmitter, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, 1999.

In his work Simon Wood (born in Bury/Lancs in 1971, lives in London) questions how facts are politicised, values defined and things exchanged and recycled. All the way from a tiny island where they work for nothing is the sentence written on a dirty carpet that also gave the work its name

Usually from an ‘exotic’ country, these carpets are woven by cheap, underpaid weavers, whose identity plays no role in future value appreciation. Wood compares the marketing process of these carpets with that of art: “I wanted to draw attention to the fact that while British art has enjoyed an increase in popularity and helped the British economy nationally, its artistic community has not really received any profit. There are so few collectors (mainly Saatchi), that the carpets represent the export of something removed from the knowledge of the lives of the people who made it.”

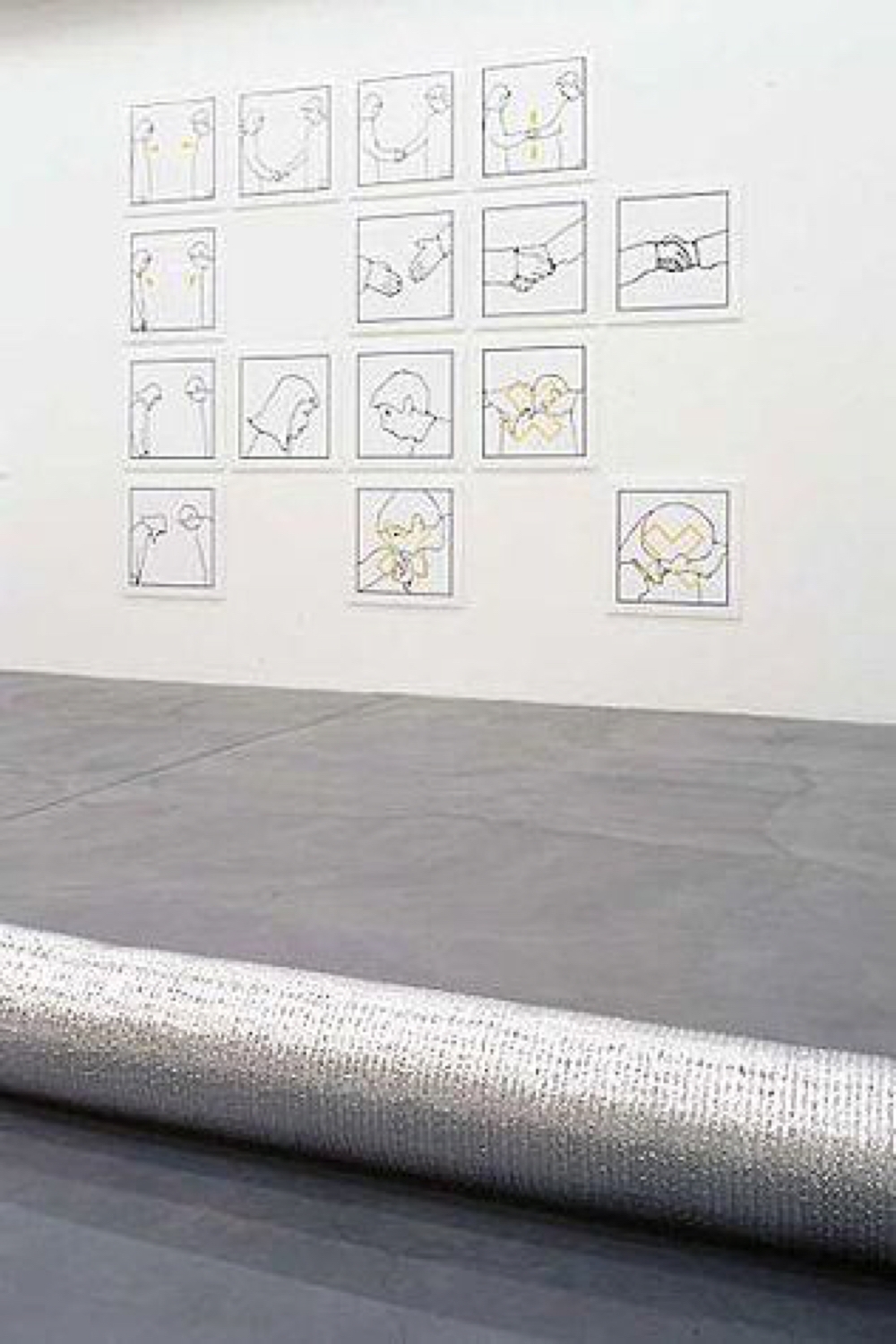

Of Chinese origin, Jun Yang (born in Qingtian/ China in 1975, lives in Vienna) grew up in Austria. His work pivots around the problems of his own origin, the attitudes of third parties and their preconceived and clichéd notions about the typical characteristics of other nationalities.

The artist’s reflections on migration and identity are analytical and executed with supreme sovereignty, but not from the perspective of a victim. A large-sized wall piece showing pictographs of greeting rituals looks like an instructions manual for the typical Asian bowing of the head and points at the fact that ‘head banging’, kissing the hand and wet kisses are social taboos that are ‘not done in public’. In the Safety cards — like the safety instructions in the front seat pockets of planes — that are a part of the work, Yang tells us about a polite conversation with a co-passengerwho mistakes Yang for a Japanese and is visibly confused by his reply that he is ‘somehow European’. In response, Yang offeres to guess the origin of the querent to which the latter said: “Yes, Polish — but I live in Germany — and I hadn’t imagined somebody would guess that.” This conversation reveals the complexity of individual feelings about one’s own origins. What led the man of Polish origin to immediately inform Yang about his place of residence, the country he has been living in for a long time? Do hierarchical considerations play a role here? How do the people of Germany and Poland perceive each other? A hair thin taboo-zone runs through Yang’s observations and even when he is not speaking of taboos one is aware of their possible existence.