Regionale 21

Mitchell Anderson, Philipp Hänger, Eric Hattan, Matthias Liechti, Raphael Loosli & Arnaud Wohlhauser, Céline Manz, Anina Müller, Alexandra Navratil, Jacob Ott, Nina Rieben, Anna Schwehr, Flurina Sokoll, Romain Tièche, Jan van Oordt, Johannes Willi, Olga Zimmelova

28.11.2020 —

4.1.2021

Asche

Candle for the no

Clouds

Coffee & Milk

Dominant Dreams

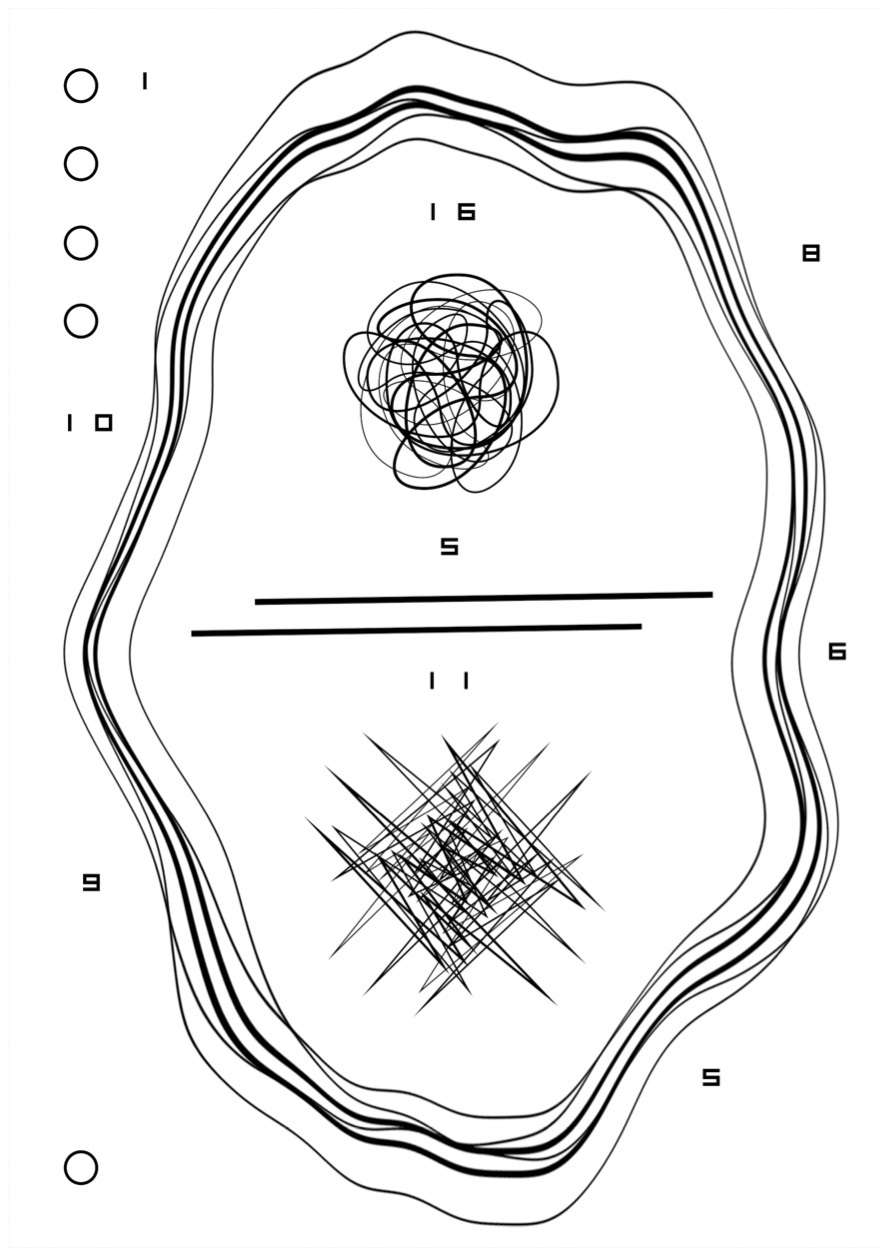

Erde an Kosmos

fold; Simulationisms

Gratis basket piece

Handlauf

Hilanderas (James S. Brady Briefing Room, White House, USA February 25, 2020)

Holes, Blanks, Ways Out

I used to like people, now I only like seagulls

in cuore sento il pazzo volo di un’ape regina

Indolore, Endolori

Im Grenzgebiet zwischen Luft und Speise Röhre

Love to love you baby

Sentimental Title, loading

Shhh

So eine Umordnung

Tête à tête

The magic is still there but the sex is terrible

The Racing Agency

Under Saturn (Act 3)

Verbeugen üben

Verlauf I

Weltenraum

A series of work titles. Reminiscent of a poem, these words unite the various artists’ works beyond their position in the exhibition. The words allow for new connections. A kind of poetry in the space, which gives us space to think: different languages, styles, and subjects invite us to reconsider the prescribed and the familiar and to connect what is separated.

The invited artists use existing resources and structures but intentionally extract individual elements in order to create new relationships through their own artistic strategies.

The exhibition at the Kunsthaus Baselland presents seventeen artists who, in an incisive appraisal of their immediate environment, pose urgent questions about our current habits and our current situation. The resulting conceptual spaces are explored by different external guests each week, who expand them with their own perspectives. Souvenir-like texts allow the visitors to remember what they have seen and to pursue some of the ideas themselves.

All artist's texts are available as free postcards at Kunsthaus Baselland.

“Gratis” or “zu verschenken”—free, to give away—appear as supposedly inviting messages on fly-tip situations by Mitchell Anderson (born 1985). The artist finds these objects in his immediate environment and, via linear arrangement in Kunsthaus Baselland, refers to similar street settings visitors would walk past with their gaze averted. The sometimes unlawful giving-away of items here highlights step-by-step the discrepancy between self-interest and generosity, revealing at the same time social and hierarchical principles. The video work Las Hilanderas (James S. Brady Briefing Room, White House, USA February 25, 2020) in the adjacent room shows the minutes before a White House press conference. At the point of intersection between politics and the public, journalists prepare for reporting, thus keeping viewers on hold. The moment of closure never occurs, the position of power remaining unoccupied. The focus instead turns towards the reporters, in the audience’s hope that they will preserve independence and objectivity. The title, chosen in reference to large-scale painting Las Hilanderas (The Spinners) by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), suggests—sometimes by way of the visually depicted Aracne mythology—that censorship and bias are more likely to occur within contemporary governments. These two positions are bound together by an interest in decontextualizing existing materials and by a keen eye for the unspectacular, emphasizing at the same time the far-reaching meaning and depth of these ordinary moments.

Previously forced to remain on the same path, two handrails from an escalator are liberated by Philipp Hänger (born 1982) and placed instead across architectural elements of the exhibition hall. With spatial reference to the existing saw-tooth roof, the handrails continue to move up and downward, running opposite the angled “teeth” of the roof. With the heaviness of the rubber-like material, the pathways seek the proximity of the floor, only gaining a playful lightness in the context of the installation. These lines shift constantly, sending out a clear invitation to move while they are being viewed and, despite their unchanged separateness, growing together into a never-final, flexible drawing in space. The tension to which they are always subject discharges in both directions into the room; in place of the circulation that would be typical here there is a decontextualization and misappropriation of the object, thus allowing a beginning and an end to be evoked. With the title Director’s Cut, the artist references a term from cinematography, thus ascribing to the switched-off object an additional, temporal moment that emerged by means of transformation. Most prominent among all of this is process, a key feature in the oeuvre of Philipp Hänger, who is the owner of a large archive of items and materials. He continually rearranges this archive, connecting its parts—following no singular path and instead thinking in all direction and forming networks.

The diverse work of the artist Eric Hattan (born 1955) has matured over decades, and it would be difficult for any observer to fix him to particular materials or genres. Videos, drawings, sculptures, and installations made from found materials — hand-sized or expanding to the scale of entire buildings, interventions into the personal sphere, the coziness of home, and even into public spaces and institutions founded by the artist himself. But the materials Hattan works with are in fact free spaces of all kinds, tracked down and shaped by him. Like a city flaneur — or perhaps it would be better here to coin the term spatial flaneur — Hattan moves through the world principally by sight. He picks up, collects, changes, adds, discards. These interventions can be large gestures or subtle, barely perceptible “rearrangements” that are bold and humorous but at the same time precise and critical, working most importantly to challenge those confronted with these new forms. In keeping with this, Hattan prefers to not provide a single work of his for exhibition and instead — as with his contribution for Kunsthaus Baselland — designs guides that do not merely define each contributed work but rather motivate another person to take action. A dialogical instruction for action, in a way; one that demands free space in one context, active creation in another, but that principally demands a totalizing reconceptualization. In each place, Hattan is there as a presence and as a creative force, exploring the nature of possible borders both architectonic and mental. But for those open to the possibility, he is principally a creative seeker of those tracks and trails upon which new perspectives and points of view become possible within old structures.

A typical garage door in Switzerland measures exactly 2.5 x 2.125 meters. Four identically sized surfaces, conforming to the stated dimensions, are lined up alongside each other on a wall. Each is formally self-contained; as a whole, however, they create a conformity that evokes a residential complex, with the protected space for the privately owned car being manifestly inseparable from the family home with which it is associated. Flat across this wall, Matthias Liechti (born 1988) has installed the letters E-X-I-T, running vertically from below upward. In countless repetitions, they merge into a continuous pattern that connects each gateway with the other, both vertically and horizontally. Simultaneously, a collective sign loses its message through subtle interventions into the direction of the text and through duplication of the uppercase letters. Interpretation of formerly comprehensible language becomes pointless; it instead lays itself ornamentally over the place to which it would otherwise merely draw attention. Holes, Blanks, Ways Out — the three words contained in the title all evoke absence. A (free) space that permits you to withdraw, fall in, fill in, or depart. Most vitally, however, this articulation describes borderline situations that catapult us in a single step from the private into the public arena, from familiar to unknown space, and vice versa. Each of these transitions brings with it expectations of a certain behavior. The artist switches focus toward these norms and conventions that govern our seeing, behavior, and especially our thought.

It has been clear for some time that the reception of many women artists of the 20th century is based largely on their biographies, reproduced in all their facets and details, formed by the zeitgeist in which they lived. This seems at times to push in front of a focused response to the work itself. This may well also be true for other centuries. The artist Céline Manz (born 1981) explores this very issue—the changing forms of reception, interpretation, and rediscovery of women artists, with a particular focus on Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Meret Oppenheim, and Sonja Delaunay-Terk. In recent years, these artists and their works have been subject to rediscovery, and they remain subject to it today. What role does an artist’s interdisciplinarity play in these works? What kind of access does it permit to each body of work? How can this body of work be accessed, and which parts of it are accessible? Hanging in the space like a flag, the artist’s work series old; Simulationisms—Limited Edition can function both as an installation and as a Travelling Edition; it sees her furnish large cloths with digitally manipulated objects from architectural drawings, paintings, and textile designs by Taeuber-Arp. Based similarly on research and in close collaboration with the current copyright and estate owner, Manz also presents an acceptance speech from Oppenheim, given upon receipt of the Basel Art Prize, in which the artist declares than many men would still deny that women possess a “creative, productive” spirit. In reprinting this speech as a free pamphlet, Manz wins visibility for it, like that of a flyer—letting it echo into the present. How are women artists today received and valued in comparison to their male colleagues?

Several voices in overlap, becoming threateningly loud, fall unexpectedly silent before sounding out once again. Text fragments like “I’m addicted to you, you’re addicted to me” are spoken by Anina Müller in a 15-minute loop using lyrics from Love Songs. In sequence and repetition, the fragments recall an interior monologue in which innumerable attempts are made to describe relationships and the feeling of love. Yet the words seems to go round in circles, losing their strength in the absurdity. Language — a means of communication seen as a way to create clarity and comprehensibility — reaches the limits of explicitness, a sign of a lack of expressive ability. How to speak about love without using the established cliches? A free dispenser stand allows visitors to take journal-like magazines marked with the words ich bin ruhig — I am calm. From a collection of singles ads, the artist extracts individual, meaning-heavy words and phrases that she then recontextualizes. “Loyalty,” “trust,” “lie,” “cheating” — all instantly classified as desirable or undesirable behavior. Expectations and desires, as held in the imaginations of many seeking a happy relationship, interrogated for their contemporaneity via this repetitive presentation.

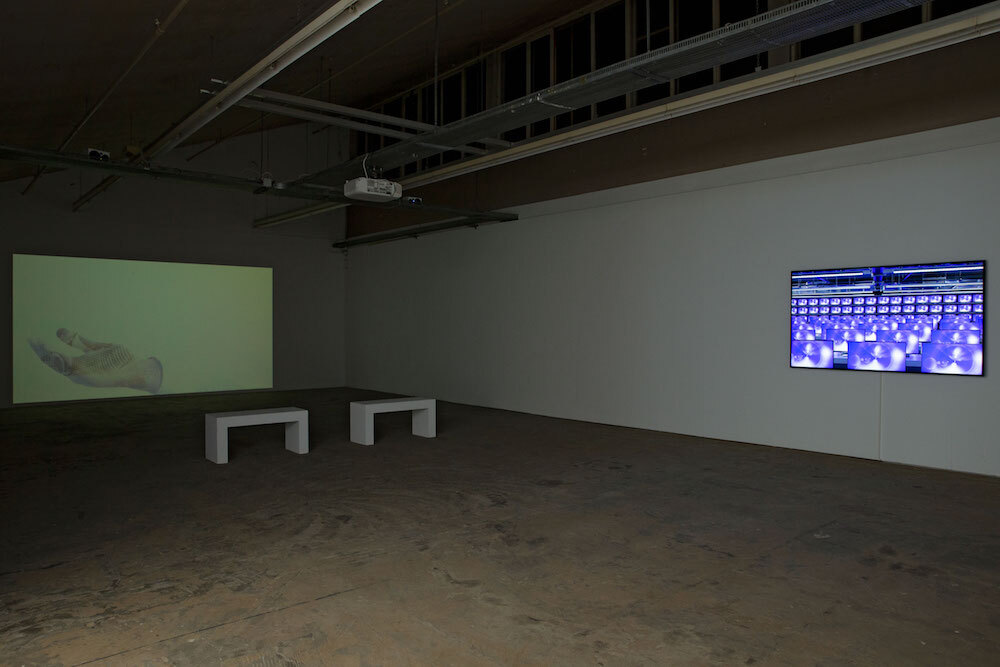

Image archives are a rich source for the creative work of Alexandra Navratil (born 1978), both in historical and contemporary terms. They provide photographs from micro or macro settings, research images, and personal shots of enormous, empty shopping malls, alongside excerpts from plastics industry journals. Based on this wealth of information, the artist has put together a large collection of images from films, videos, and photographs, in pursuit of the question of how our perception works, how it changes, and which technologies accompany and influence us in our perceptions. Her Under Saturn (Act 3) thus entraps the viewer with its highly technological but at the same time emotionally charged images. The confidence-inspiring voice in the collected and overlapped ad images — taken from various robotics companies’ brochures — create a dreamlike, frightening message. Does the voice not tell of near-death experiences? Where is the flesh-and-bone human being to be found?

The video Phantom (1) also provides a view of a deserted electronics megastore. Powerful natural phenomena are looped on-screen, staggered one after the other in glossy resolution. The title is a reference to a high-speed camera of the same name that records at between 1 and 1000 frames per second and is often used by anonymous makers to create generic recordings in extreme slow-motion. Presence and absence also characterize Alexandra Navratil’s work; in a minimized but at the same time visually powerful way, she manages time and again to create intimacy and distance to those stood opposite, confronting us with sight and being.

The arrangement of the Mkv III-VI displays, which function as containers, lends the Cabinet Room a new rhythm that can be experienced as a space-consuming assemblage. They are placed within the space such that the elements, created from found construction materials, develop their own geography, consciously guiding the public as they pass through. Jan van Oordt (born 1980) thus makes it possible to experience situated overlaps of meaning, brought into relation with one another by the individual works. The decontextualization that his found materials and forms undergo thus establishes links to unfamiliar environments. In a corner setting, two rotating slide projections encounter each other, each taken from collections of formally similar patterns. Wasser im Wasser [Water in Water] shows a range of entrances to animal dwellings. They remind us of places and subjectivities that remain inaccessible to humanity. Inherent to them, as with the objects touched by hands in You, is a fragile connection that enables access to innumerable (interpretive) openings.

The threshold emerges as a recurring moment, drawing a conceptual thread through the artist’s entire space. Always describing an in-between place, the threshold brings with it a constant opening and closing, a relation from interior to exterior and vice versa, and often enough also a point of intersection between the personal and the public. Jan van Oordt translates this interest in transitions—hollows, touches, animal transformations, and the edges of the forest—into a spatial installation. He at times allows viewers to enter into interrelations of meaning from various plateaus, seeking to never achieve any finality in the interpretation of things.

Jacob Ott (born 1992), in two site-specific works, forges direct links to the architectural qualities of Kunsthaus Baselland. The artist closes off the ground-floor entrance with an almost three-meter wide band at eye level, compelling visitors to walk different directions. Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the paths upon which they are guided are in the form of oversized, strung-together pretzels. A highly symbolic shape which, per the origin of its name (from Latin brachium or arm), is meant to remind us of folded arms. Thanks to the notches presented by the repeating patten, the background remains visible, permitted to function as a key part of the ornamental image while also allowing light to shine through the pretzels, a foodstuff historically used as a fasting meal. Taken in their totality and depending upon the angle of view, they can transform from a symbol of abstinence into a decorative loop, resulting in an inversion at the level of signification.

By way of a subtle intervention onto a wall located behind, the artist creates a renewed reference to the architecture, consciously influencing how it is perceived in space. An angled fluorescent tube runs from the ceiling to the wall, lending the existing lighting the appearance of an object. The ceiling itself, like the free-standing wall module, functions as a display, with the architecture itself becoming an installation. Highlighting each opposed function thus brings the familiar into focus, simultaneously unsettling the foundational principles of the space in a way that evokes the swallowing found in the work Im Grenzgebiet zwischen Luft und Speise Röhre [In the Border Area between Air and the Esophagus].

White, empty spaces. Blank spaces in a darked and at the same time brightly lit space, appearing as placeholders for the unspoken; for possible words and texts. In large-scale photographs by the artist Nina Rieben (born 1992), rectangles are raised up against the backdrop of sundown settings. Captured by a reflection on a pane of glass, they complicate the relationship between interior and exterior — between closeness and distance. Foliage is scattered across the floor; the title Romance might be a competence makes subtle reference to the sparse trees beyond the window and a message on a phone’s screen. Addressed to an unknown person, my dear (Trennungskompetenz) [separation competence] narrates leaves’ effortless “letting go” of autumnal trees. This annual separation comes with a change in natural light that brings with it at times the supposedly romantic moments of the fall season. On some of these leaves, the artist has rendered a specially developed and encoded handwriting. Visitors are unable to decipher the code of the loose characters. But the intention is not for them to find a solution but for them to recognize that the explicitness of language is limited; a fragile, candle-like object refuses to be ignited and acts instead as a reverential symbol of pessimism. The lighting conditions experienced prior are reversed in the next room. Darkened windows, now lit and instigating changed perception due to the previously absent light. It is with a precise juxtaposition that Nina Rieben explores settings of bright and dark, light and shadow. These have social and linguistic connotations often associated on one side with positivity and joy, on the other with melancholy and bleakness. In this, the artist always retains room for fictional narration; by consciously subverting relations, she questions the cliched aesthetics of poetry and sentimentality.

It is with a slight lowering of the upper body that the completion of work is accompanied with a bow of thanks. The expansive Verbeugen üben [Bowing Practice] installation by Anna Schwehr (born 1992) refers rather to the moments before the bow. There is a sense here that physical exercise could begin immediately. But small details such as the canvases concealed as mats hint that these elements only simulate the absence of some essential thing: a body getting itself fit. The metal construction forms a diagram whose heights and breadths are drawn from rules determined by the artist. Crucial here are physical (body) masses, but also actions that she performs—including those that involve doing nothing. Juxtaposed, they form a dynamic that highlights the economy of an individual’s fitness regime. Anna Schwehr melts down bronze busts of Karl Marx and Lenin, transforming them into dumbbells, thus shifting this isolated memory of two historical individuals into a way of performing bodily exercise. This goal of getting fit, encountered here with irony, is followed by a questioning of conformism, hidden within the translation of the term “to fit” into German as “(an)passen”—to fit, but also to adapt. The spoken works of a horseracing commentator bring an additional restlessness into the space. The video work shows quickly interspersed images of equestrian statues in competition with each other. Entering the stage anonymously, these fossilized bronze statues—influenced by the off-stage voice — compete in a race despite their immobility. The trial of strength is rejected in an act of humor, with the gaze being directed to forms of interaction that bring with them more solidarity.

Ephemerality adopts a particular material form. In their very means of production, many everyday objects are of a non-permanent character, thus encouraging constant consumption. It is in this abundance that unused objects find their way to Flurina Sokoll (born 1986). The work Tête-a-tête beings as soon as the space is entered; around a corner, two chair frames are stood opposite each other, connected with a single sheet of wood. A dark coat is laid over a backrest, a gift to the artist. This weight is counterbalanced on the other side by an enthroned white glass ball. Several steps further, a radiator is installed in front of a white, net-like curtain; on top of this is placed a figurative-looking object made of fabric, a belt, and an object whose figure suggests that of a metal shell. The artist makes no major interventions into the individual items, with their multi-layered levels of meaning instead being drawn from arrangement into certain constellations. These connections are not definitive and can instead experience new combinations with the passage of time. For Coffee & Milk, a converted metal bed frame provides support for a worn-down table surface, on top of which are placed a coffee-stained pillowcase and a vase. A wall surface painted in the shade of light sand and a number of doormats create a spatial setting that shifts when a viewer passes by, thus refuting any still-life associations. Fragments from a remarkably diverse range of contexts come together through Flurina Sokoll; they bring with them a story inherent to them but which in arrangement recedes into the background, driving the focus instead towards formal and material qualities.

The influence of technology on humans, the knowledge thus associated, and the aesthetics derived from this are key themes for Romain Tièche (born 1982). Across two large-surface displays, observes encounter the terms “indolore” and its opposite “endolori”—respectively translating into English as ‘painless’ and ‘painful.’ In this installation, Tièche plays with simultaneity of antonyms and anagrams, with the mere inversion of the first and last letters rendering each term as its opposite; a phenomenon is unique in the French language. In a brief moment of subliminal perception triggered by a blurring of the video, a new image is inserted between the letters, dissolving the anagrams. This blink-of-an-eye moment is repeated continuously, until the two terms overlap and the positions swap over. The artist deploys a method from marketing, in which the customer is influenced subconsciously. The expressive aesthetics of the black uppercase on a white background are modelled on the warnings found on cigarette packaging, which provide a paradoxical warning against what the packaging itself contains. Indolore, Endolori thus reflects the perversity of propaganda—the interplay of production consent and injunction—embodied in those marketing techniques.

With The Racing Agency, Johannes Willi (born 1983) issues an invitation to a Sunday bicycle ride. Together with the invitees, he visits exhibitions on a tour of participating art institutions. The unifying element here is a cycling kit designed by the artist and worn by the group, who thus bring a flexible image into the three-country region. Departing from Kunsthaus Baselland, the kit design contains spatial views of the empty exhibition building, thus showing possible locations for works. These architectural fragments form collages around the bodies of the cyclists; these bodies themselves then become a display, bringing the existing white cube into new contexts and taking everything in their immediate environment briefly as a backdrop. Simultaneously, the looseness of the structure—having appropriated the experience of distance and the landscapes travelled—opens up a mobile exhibition space filled with thought and conversation. At the present time especially, this serves not only to provide the artist himself with a way of developing new ideas beyond architectonic limitations, here transformed into flexible structures on clothing: it also brings into clearer light the vitality of maintaining in-person contact. Willi, who recently founded a cycling club by the name of VC Madonna, brings the Kunsthaus into the region, visiting new interiors along with the invited riders, thus inducing a continuous interweaving of the interior and exterior. To external observers, the group can present itself as a cycling team, as exhibition visitors, cultural ambassadors, a display, and not least as a living, moving artwork.

In the semi-darkness of the last exhibition room, visitors encounter a shut chest freezer. It can be opened and closed via its handle and is completely filled with frozen water. When opened, the surface of the ice is subtly illuminated by the built-in light on the inner side of the lid. The interior results of this icing-over are shown at the moment of the exhibition; an icing “ritual” Raphael Loosli & Arnaud Wohlhauser (born 1980/1992) carried out for the first time in January 2016. For a brief time — the duration of the exhibition — the artists are creating a performative rearrangement of this of this common Satrap-brand deep freezer. The continuous hum of this mechanical household appliance reflects work to be done. Locating the deep freezer in Kunsthaus Baselland can create an oppressive uncertainty within visitors, compelling them to penetrate into the interior. The title the magic is still there but the sex is terrible — a reference to an American cartoon — conveys the fragile balance of a relationship; a balance that can be transferred both to shared rituals and to the interrelationships of artists, space, and visitors.

Superimposed and wafer-thin brushstrokes create a dense, multi-layer form of painting — a brushstroke image, painted directly onto the wall, that subjects Kunsthaus Baselland to rhythm. The white, almost-transparent brushstrokes seem cooling across the light-blue background. Olga Zimmelova refers here to bees’ temperature regulation within the hive; when the temperature is high, they vibrate their wings above the honeycombs to create a cooling effect. A dark, heavy presence at the lower edge of the image makes reference in turn to the emergence of new life in the honeycomb. Five honeycomb objects are brought into spatial relation with painting while the artefact — a beekeeper’s frame prepared by the artist with brushstrokes and textual quotations—is combined with the bee-produced honeycombs. The painting and quotations, including the sentence “Non andar nudo a torre a l’api il mele” (“Do not go naked when taking honey from bees” — Giordano Bruno), are covered to differing degrees by the honeycomb and are only partially visible. Objects and brushstroke images evoke associations, interpretations, and perceptions, looking at the bee as part of cultural history.