Keywords and the powers of eloquence

Wie in der Sprache Macht und Identität verhandelt werden

How power and identity are dealt with in language

15.9. —

11.11.2012

The thematic group exhibition Keywords and the power of eloquence, conceived by the free-lance curator Nadia Schneider Willen for Kunsthaus Baselland, deals with the complex relationship and interactions between language and power. Established as well as younger artists from Europe, the USA, Latin America and Switzerland deal with the theme through drawings, photography, video, text and audio installation.

The powerful have the final say, goes the saying, or in other words: “He who has the language calls the shots.” The struggle for power is often a battle for the prerogative of interpretation and an attempt at the same time to silence the opposition by argument or force. José Restrepo's video El arte de la retórica manual (2010) expresses this without words: the speech of a politician in the Colombian Senate, apparently delivered to persuade his audience, remains silent. Only its expressive gestures were set to music and his monologue is punctuated by loud thuds of the hands on the lectern.

Several video works and an audio installation of Tania Bruguera also deal with the fact that the language, as the most important code of social understanding, is exploited in political discourse as no other communication system. In Autobiografía — Inside Cuba (2003), huge speakers boom short clips and keywords of Fidel Castro’s eloquent, epic speeches, while a solitary microphone on an empty stage invites the audience to rise to speak. That this is only seemingly possible and bold speakers hardly had a chance to speak against the verbiage of the powers that be is illustrated by the fact that the microphone is not at all amplified.

If what is alluded here is a strategy of dictatorial regimes which deliberately uses an aggressive rhetoric to deprive the addressees of their own intellectual freedom and thus gain control over language, Julika Rudelius’ work is situated clearly in a democratic system, where persuasive strategies are rather also used to enforce its own interpretive framework. In Rudelius’ double projection Rites of Passage (2008), created out of documentary footage and staged sequences, she shows dialogues between influential politicians and their interns. In this verbal exchange, the expression of the balance of power between teacher and student, among other things, refers to the model of “charismatic leadership”, which places a fascinating appearance, personal charm and rhetorical assertiveness above the delivery of a compelling content or an independent vision.

Lena Maria Thüring’s recent work that has been designed especially for the exhibition also refers to the aspect of self-staging as a political personality. In a casting recording studio in Hollywood, she makes actors give a political “election speech”. The texts are taken from songs presidential candidates have used in the election campaign. Here the discrepancy between the content of the song that should represent the candidate and the actual political programme in certain cases is so glaring that one might wonder whether the potential head of state had ever taken the trouble to listen to the song beyond the chorus and the stirring tune. Why else would, for example, Ronald Reagan have chosen for his 1984 election campaign the anti-war song Born in the USA by Bruce Springsteen?

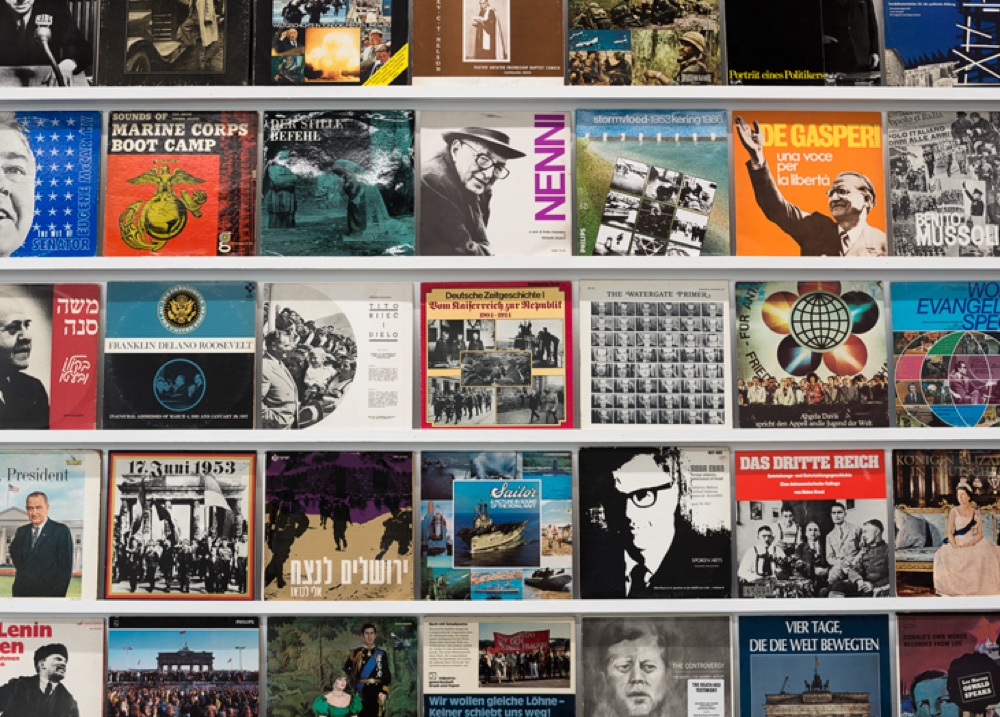

Important speeches of presidents and interviews with world leaders, peace accord and human rights debates and radio broadcasts from the 1950s to 1980s are combined in the collection Historical Records Archive, which Dani Gal has been compiling and continuously expanding since 2005. Most of the sound clips from the over 270 LP records documenting political and historical events of the 20th century were used as propaganda and were of central importance for the establishment and dissemination of national historiography.

Other works in the exhibition explore how at a societal level, where both political and personal aspects come into play, each of the different speeches embody a different symbolic capital and thereby define the status of the speaker. Because, there is nothing much revealed about our origins, our social status and our educational background as our language(s) and the manner in which we speak it. The people in Katarina Zdjelar's video, A Girl, the Sun and an Airplane Airplane (2007) attempt to bring out isolated words in Russian from their long-term memory in a recording studio. These people had to learn this language during their school years in Albania. They embodied at the time, during the Enver Hoxha regime, an ideology with which one had to identify themselves, and which augured hope for a better future. The forgetfulness of this language that is no longer spoken today in Albania is not just an individual, natural process, but one that is associated with the social distancing from the ideological content and value systems which symbolised that idiom.

Just as speaking the ‹correct› language in a certain context promises success, the opposite can be a factor of social or political discrimination, which in turn points to the existing power imbalance between different language groups. In The Last Silent Movie (2007) Susan Hiller opens an archive of languages that are endangered or have already become silent. Based on recordings that were made for anthropological research, the work speaks not only about the disappearance of languages, peoples and cultures, but also about the power structure that has contributed to this disappearance.

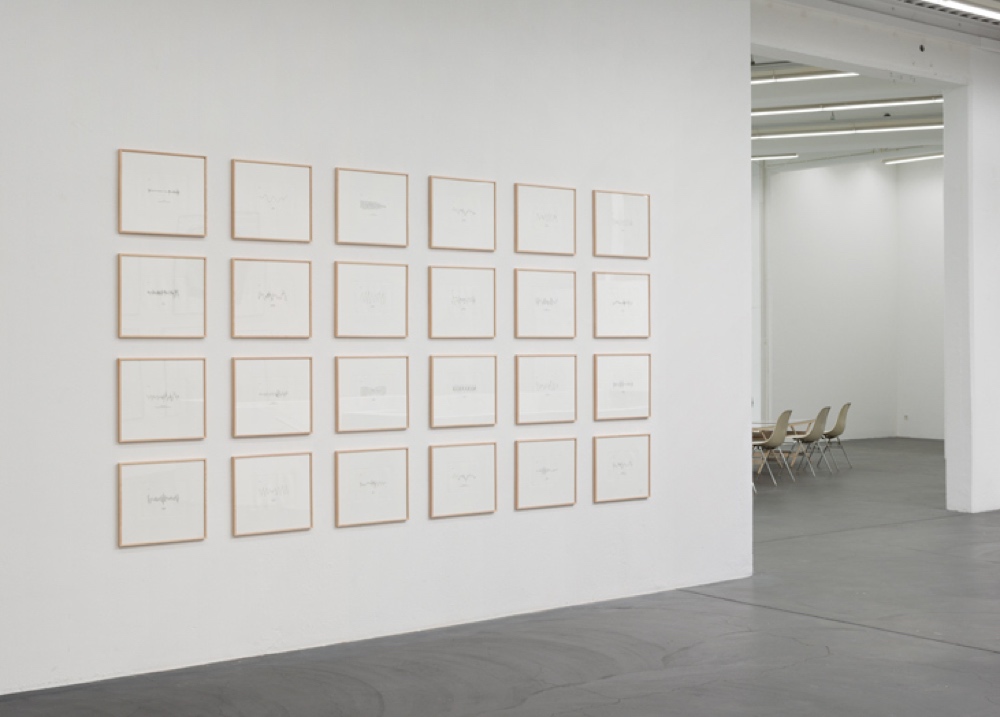

Not mastering a language or being illiterate also determines the social rank of a person and draws an imaginary boundary beyond which there exists no potential for social advancement. The graphic notations of Yto Barrada’s grandmother, which the photographer included in her series of pictures The Telephone Books (or the Recipe Books) (2010) are, therefore, much more than just doodles. These are mnemonic sketches that the woman used as an illiterate to remember the most important phone numbers — a kind of substitute characters that convey the detours and ingenuity necessary for compensating the drawback.

Aspects of the constitutive role of language in the formation of a personal or cultural identity are expressed in the works of Sharon Hayes, Daniela Keiser and Goran Galić / Gian-Reto Gredig. In the four monologues, which Sharon Hayes reproduces from existing video tapes from the 1970s (Symbionese Liberation Army (2003)), the kidnapped daughter of a billionaire, Patty Hearst, expresses her solidarity with her captors more and more, from one recording to the next, and ultimately takes on a new identity. The speech itself, the fumbling generation of a monologue, is indeed a theme as well in this work, yet Hayes lets an unseen audience correct the memorised text halfway through and prompt when it deviates from the text or loses the thread.

Daniela Keiser in her Ar & Or (2010) makes ten people from the European cultural area with relations to the Arab world write fictional biographies of a young woman from Cairo. To serve as a basis, there was only the photograph of a conservative Egyptian girl, but in "modern" clothes, playing the "blind man's bluff" in a park. The texts are in the original language as well as translated into Arabic, can be read on ten tables, together with the prints of the said photograph, which were produced by different printers in Cairo. If the artist’s work is called ‹translation project›, then this is not only a description of a linguistic process, that is, the transfer of a text from one language to the other. In reality, the question moreover poses the possibility of the transfer of cultural concepts and social norms into other contexts. How do we read an image that comes from an unfamiliar frame of cultural reference, and to what extent are we able to interpret this?

The difficulties of intercultural understanding is dealt with in the video work newly created for the exhibition by Goran Galić and Gian-Reto Gredig. In advanced training workshops of large companies, with titles like How to negotiate with Arabic / Indian / international business partners, they observed the well-meant but also somewhat helpless attempts to convey in a simplified and concise form culturally shaped, social norms and behaviours in very broad cultural groups such as that of the ‹Arab world› and to instruct us on how to act or negotiate and communicate in certain situations. The works by Fiona Banner and Jorge Macchi also deal with translation in the broadest sense — the transfer of characters of one system to another.

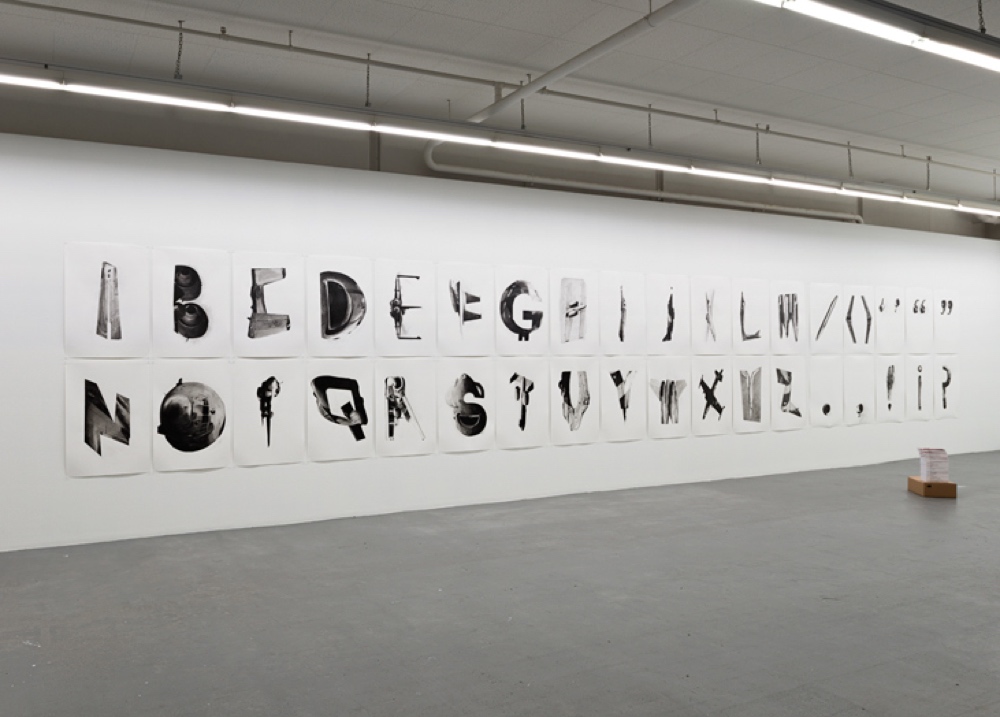

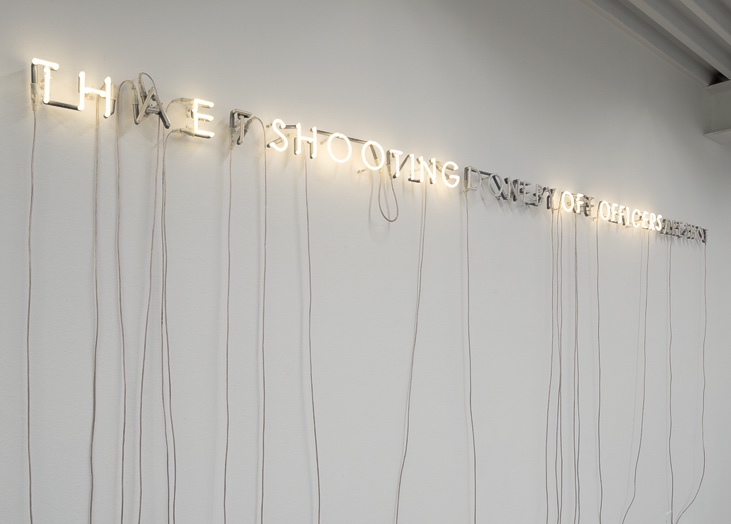

Fiona Banner has created an alphabet in large format drawings, The Bastard Word (2006/07), which consist entirely of elements of fighter jets — a war machine that symbolises power and violence like no other. These combat machines that arouse fascination and revulsion at the same time become characters of our sign system here and thus the basis of any possible statement. In Jorge Macchi’s 12 Short Songs(2009) in contrast, headlines from American newspapers, which mostly refer to the economic crisis, become punch card perforations which are rotated through a music box that make strange-sounding and yet familiar tones.