Collectif_fact

12.8. —

30.11.2007

The Geneva-based group of artists Collectif_fact presents its first institutional solo show in Kunsthaus Baselland’s underground-level rooms and Shedhalle. Annelore Schneider (born in 1979 in Neuchâtel), Swann Thommen (born in 1979 in Saint-Imier), and Claude Piguet (born in 1977 in Neuchâtel) have worked together since 2001, after they had met at the Ecole supérieure des beaux-arts Genève.

Collectif_fact create their works by using a sophisticated digital sampling technique. Similarly to processes for composing electronic music, elements and tiny fragments taken from photographs, videos, digital data sets, and image databases are isolated, cut out, transferred, multiplied, reassembled, deprived of their original spatiality and physicality, and thus placed in entirely new contexts and non-narrative but quite coherent sequences of images. The group’s works reflect a digitized society in which a parallel, interchangeable life is possible thanks to standardized, virtual, formal, and functional elements. For all their virtuality, direct links to reality remain since what emerges emanates from a real experience. The works’ content is what makes them so intriguing; Collectif_fact, thanks to their meticulous observations, are able to articulate contemporary social phenomena with great poignancy.

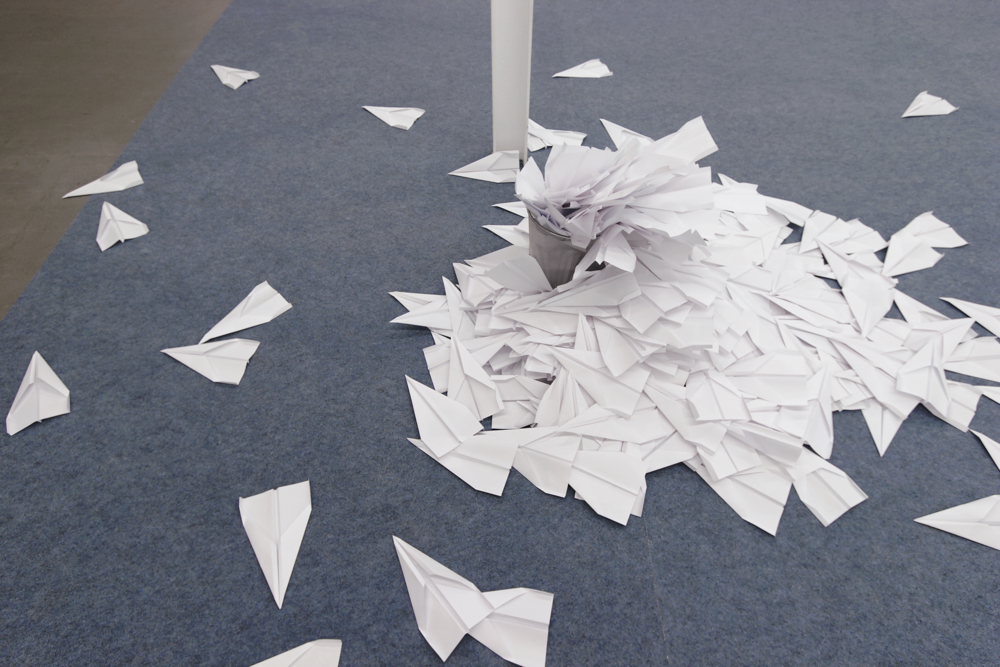

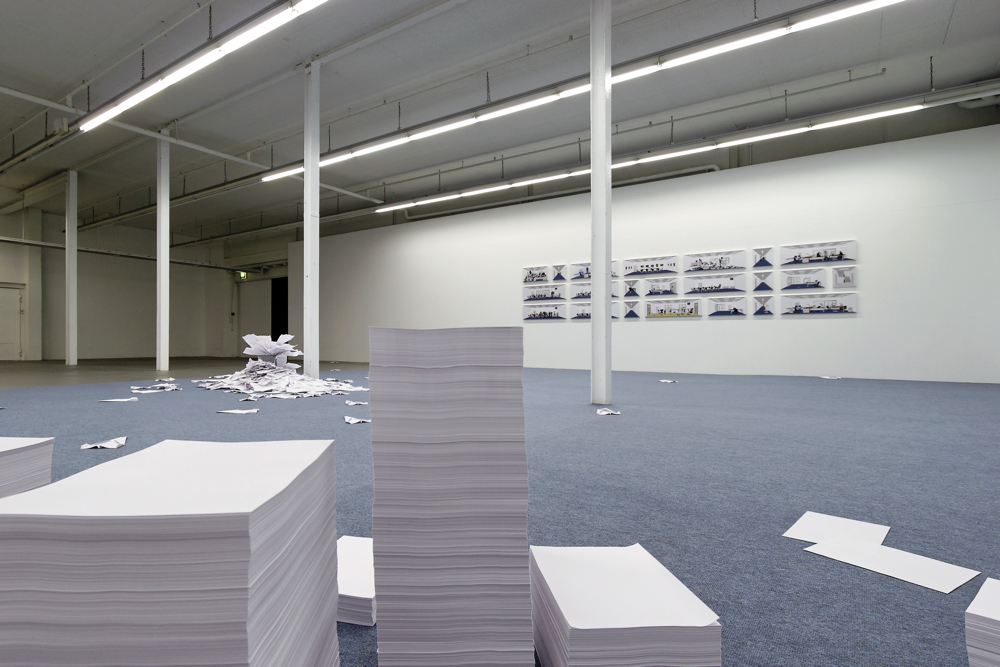

At Kunsthaus Baselland, the group presents its sweeping installations Ce qui arrive (2005/07) and Reliefs (2005/07) merged with Drag & Drop (2006/07). Collectif_fact reconstitute existing works by adhering to their own principle of creating art, while also allowing for other interpretations and new visual experiences. Their series of photos entitled Ce qui arrive revolves around the fundamental notions governing office furniture and equipment as well as the mood prevailing in working environments with a functional focus. The rooms designed by the artists come with standardized furniture. They are functional, impersonal, and interchangeable. However, what distinguishes them from regular office rooms is that they also feature another set of standardized, and yet incongruous, equipment — things you expect to find on airplanes such as oxygen masks, life vests, illuminated emergency exit markings, and slides. These objects make an office and an aircraft environment morph into a utopian space that radiates a sense of foreboding — the feeling that something calamitous is bound to happen. The installation in which this series of photographs is presented captures this mood precisely. The spatial setting with its office carpeting, several stacks of paper, and an overflowing garbage can filled to its rim with paper planes seems to reinforce what the photos announce: “Ce qui arrive”. “What may happen” is an apt description of today’s society shaken by the fear of terrorism and marked by distinctive value systems.

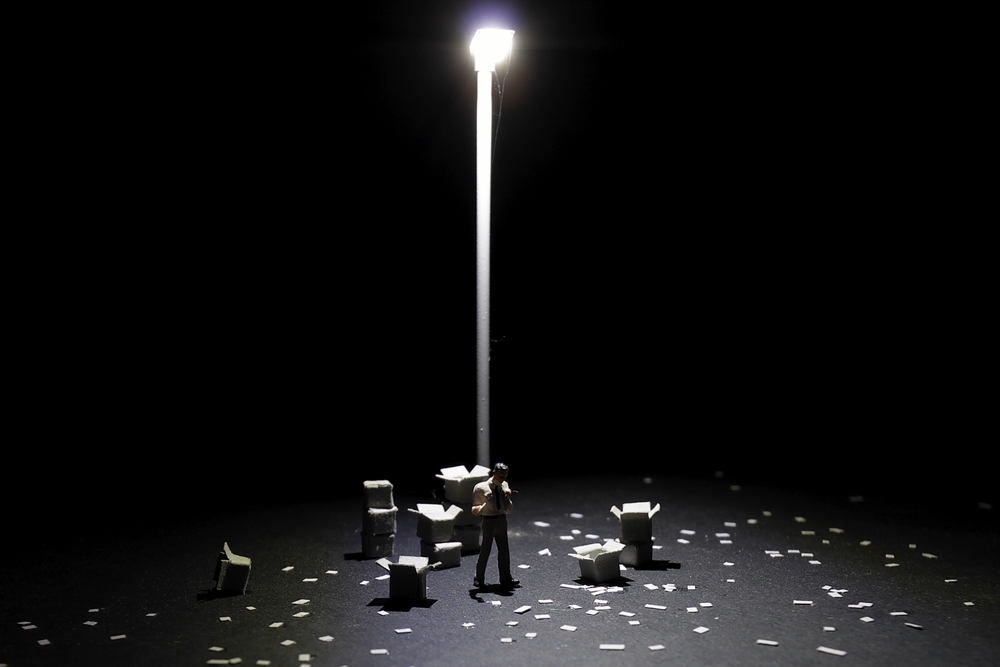

The two works Reliefs and Drag & Drop are presented in an entirely new format. Originally on display at separate locations, they are blended into one big installation at Kunsthaus Baselland. In a room cluttered with real objects reminiscent of virtual, artificial trees made of cardboard, there is a garden shed tucked away in the most remote corner, one side tilted below floor level. On closer inspection, the light flickering within turns out to be the video Reliefs. The garden shed, originally a categorized, prefabricated model, is subjected to a drag-and-drop procedure by Collectif_fact. This technique, which is applied in digital media, removes something from its original context and inserts it elsewhere. In analogy to this technique, the components were not assembled according to plan here; much rather, mistakes were made quite deliberately. This exercise resulted in a shack that has partly sunk into the wall and the ground. The viewers’ imagination begins to falter, and this teetering is compounded by the cold, deserted, and comatose mood prevailing in the video. Reliefs combines the formal and stylistic repertoire found in the works of Collectif_fact: Scenarios marked by shades of gray, dappled with urban elements such as vehicles and components appearing in relief, colorful and illuminated advertising signs, light sources that shine on nothing but emptiness; abrupt switches to another spatial level; no story is told, there is neither the past nor the future; even the present skips from one spatial fragment or snippet of content to the next, with no transitions in between.

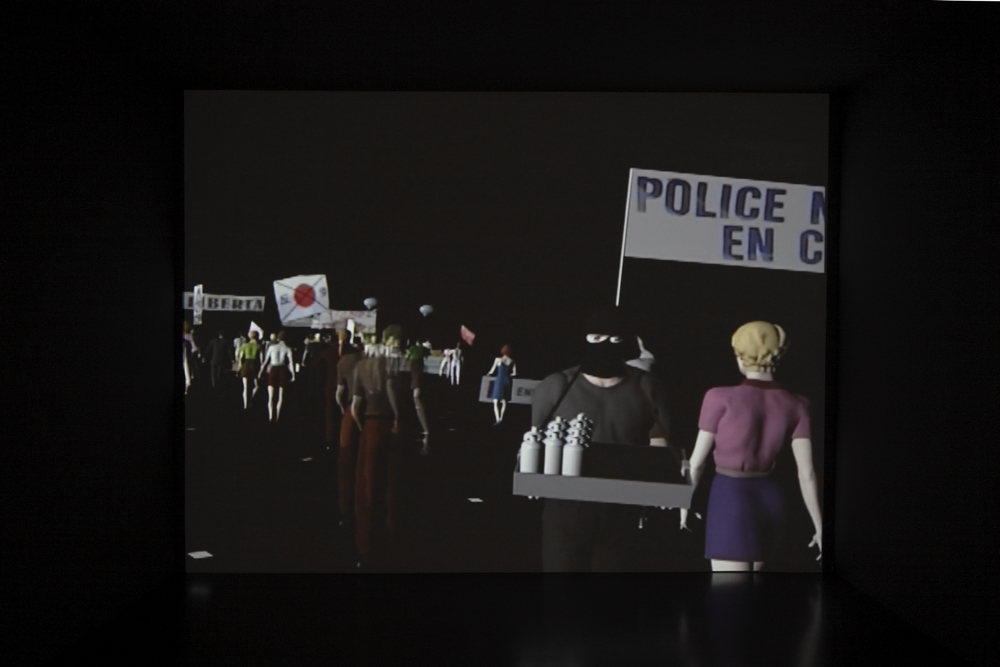

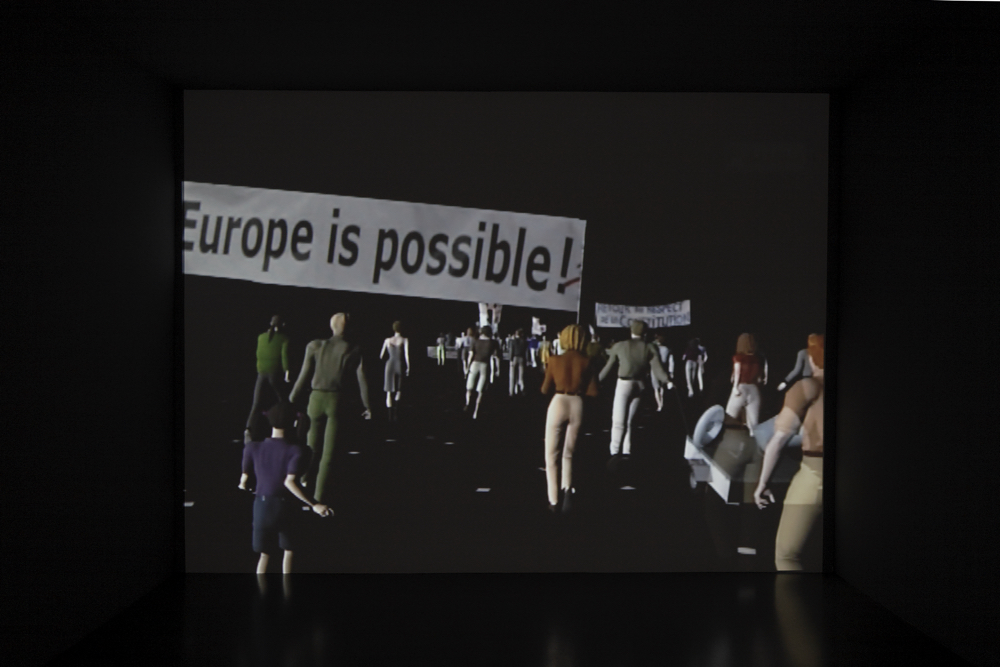

The installation XIT (2006/07) features what appears to be a door partly built into, and hidden by, the wall as well as a fragment of an ‘emergency exit’ sign. It pursues the same artistic strategy as Drag & Drop. XIT, placed next to the stairwell, casts an ironic glance at the function fulfilled by the original sign. The implied emergency exit literally ends at the wall. Another video — On Stage (2007) — picks up the topic of political demonstrations. Standardized figures that look like toys and crop up repeatedly like visual markers march in the same direction, with great equanimity, and without generating any noise or displaying any emotions. On the banners sported by these figures demands are made such as “No person is illegal” or “Viande meurtre”, and these slogans connect the virtual scenario to reality. References to works created by fellow artists tout art as a forum conducive to political statements: One banner which reads “On est tous coupable” has the signature of artist Ben Vautier; “I am Desparate” is a direct allusion to Gillian Wearing’s “Signs that say what you want to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say”. The calmness and serenity exuded by this video stand in stark contrast to noisy real-life demonstrations. Considering that demonstrations are largely neglected in media coverage and often associated only with traffic jams, this video may also be construed as a form of criticism leveled at the media. The only disruption caused by this eerily quiet protest march is the sudden interruption of the video, as if a camera had been knocked over. This is where the scenario takes an unexpected turn, and a sense of danger, present only subliminally, briefly comes to the fore.

“The digital age is dominated by numbers; everything is replaceable and interchangeable. Images replace objects, what is perceived is the substitute for what is concrete, and media coverage has supplanted real life. Viewed from a distance, Collectif_fact conjure up an all-pervasive sense of inevitability. They make us yearn to break free from a system that relies on a voluntary surrender of freedom and the humiliating realization that we are all just ants soldiering on no matter what.” (Simon Lamunière)