Piero Golia

The Painter

28.4. —

16.7.2017

The first comprehensive solo exhibition of the Los Angeles based artist Piero Golia in Switzerland.

You could say that to try to implement a traditional exhibition with Piero Golia is well-nigh impossible. Thankfully. Because the starting point for all his artistic reflection is the whole system of art: how artists relate to it, its processes and, in particular, the choreography of the individual actors within the system. He observes, and in so doing challenges its forces and its norms, how institutions operate and their expectations of cultural producers. But for him it is also about sounding out the boundaries that prevail when dealing with an institution or a structure, in so doing also testing its porousness. This is why, for him, an exhibition does not entail a display of work, but rather discussion, food for thought, a change of perspective, communication and, ultimately, one thing: creating a theatrical moment using unexpected situations.

This can be retraced from many of Golia’s projects realised over past years. In around 2005 Golia co-founded the Mountain School of Arts in Los Angeles, a school where the students could learn and take part in lessons without having to pay any fees. This school is still active today and invites international artists to give workshops and lectures. It is a long-term project, through which Piero Golia also committed to making his home there permanently. Then in 2013 Golia brought Chalet Hollywood to life, in Los Angeles. It is a kind of club which is adorned with loans and works by artists he knows, a place to experience art that operates by generating exchange through conversation. But it was also a place to consume food and drinks sociably, and, essentially, for free — for a year and a half. Easy to imagine that this could threaten a budget. Invited by the Hammer Museum, Golia, together with a group of art students, recreated the nose of the first US president George Washington from Mount Rushmore in 2014. Once again a project of tremendous scale, with which Golia expressed the production of art as a theatrical act. In many of his projects the end result is not primarily front and centre, but the process of arriving there instead. At the end of this process the artwork is not the essential thing for Piero Golia, but rather the act of its creation and the exchange with other people that is involved. The project Luminous Sphere has been running since 2008. A brightly shining, spherical fluorescent light at the height of a Standard hotel in Los Angeles is activated by the artist when he is in the city. An individual means of communicating within the metropolis — independent of mobile telephones and social media. One of Golia’s key artistic motivations is putting things in relation to each other in order to be able to comprehend their complexity in the process; an exhibition or a project can be the catalyst for these very processes. In his work, art is challenged to see if it possesses this capacity to build a strong social fabric, to make us communicate with each other and to throw light on the structures within which we operate. It is obvious that a traditional exhibition cannot simply take place, thus.

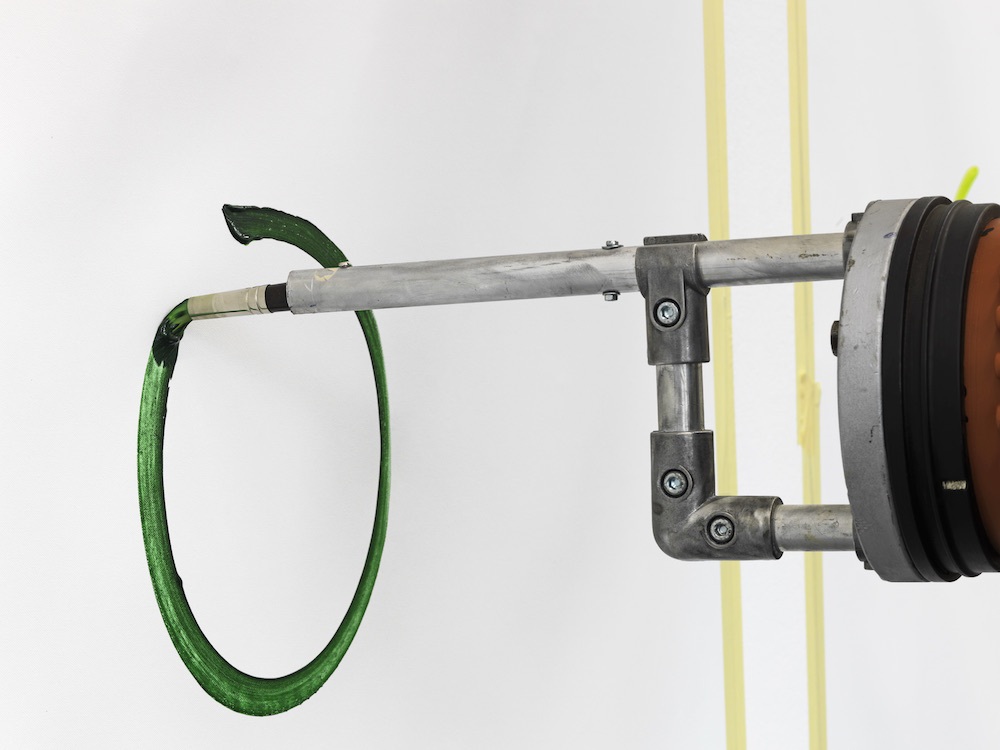

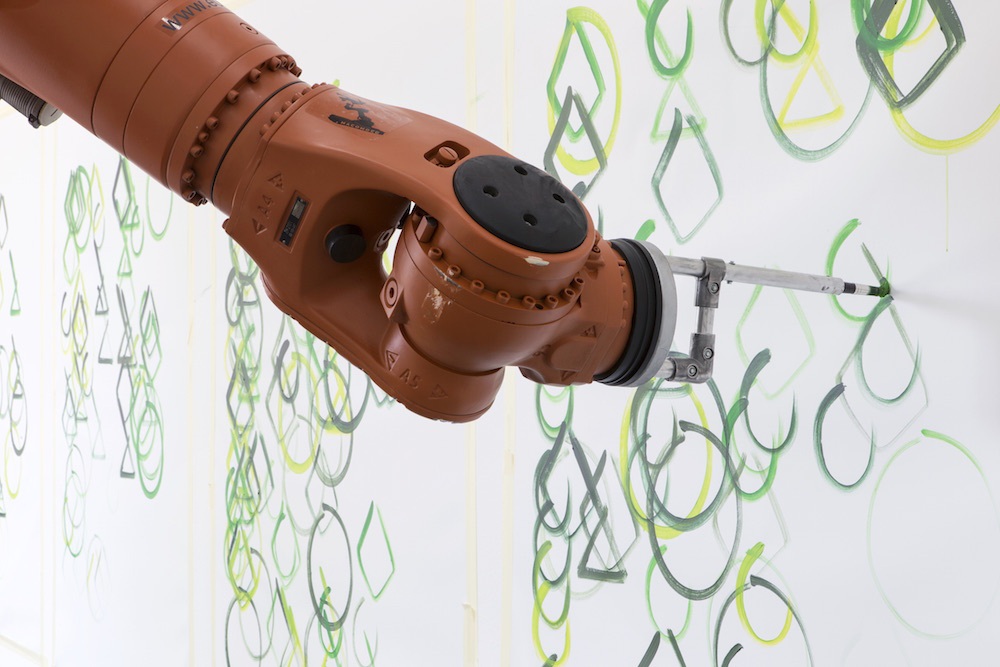

So now there is an invitation to realise a work at the Kunsthaus Baselland. Golia has a particular choreography in mind which also incorporates the fact that one of the most important art fairs will take place in Basel at the same time. In one of the many conversations that follow the first meeting in Rome, Golia describes how art has become merchandise, destined for commerce. Even if it was not always this way, today we are almost back to the 1980s. Art is sold by the square metre. “So I was interested in breaking the numbers,” continues Golia. Here “breaking the numbers” means producing something large-scale as effectively and extensive as possible — in the literal sense of the words. Maybe it also means going beyond the usual proportions of an exhibition and thus perhaps reaching the limits of an institution, one that can only master his project when it musters all its powers. So emails are sent back and forth, calculations are made, we think, check and talk lots more. And then it is standing there — a robot weighing several tons on its 14 metre long track. A whole arsenal of cranes, forklifts and people hoists it into the Kunsthaus. Stress analysts and transport companies check whether the floor will withstand the load. After the robot, which has come from the milieu of the film industry in Rome, has been programmed over several days it then does the thing for which it was activated — it paints. The theatricality of it cannot be ignored. “Abstract painting,” Golia remarks, “is all about theatre; if you think about all the images showing Pollock in his studio, for example, pouring paint on canvas which lay on the floor. But something that interests me here as well is this idea of narration. As the robot reacts to the people who enter the space — one after another they break the normal story of the exhibition. In the end, the paintings will tell you the story of the exhibition. So the painting can be understood as a narrative.” What interests Piero Golia above all in this highly specialised machine, one which seemingly replaces the artist and which sometimes appears human in its movements, becomes visible as soon as you enter the space, the robot starts to move along its track and you can hardly take your eyes off it for a second: it is art as a theatrical act. How it swirls the brush through the air, bends backwards briefly, hammy and elegant at once, and then dips the brush in the different blue and green acrylic paints with almost unprecedented precision.

Over days, weeks and months it will describe various geometric forms on the eight large-scale canvases laid out in front of it along the nearly 30 metre long wall. Again and again it will slowly allow its robotic arm to glide into the different pots of paint placed in front of it and follow its choreography. Golia would be misunderstood if one were to think that he is realising this conceptually envisaged project merely for the sake of its theatricality. While the machine is producing large canvases in the exhibition space with its extrovert gestures, only painting and being active when the public is allowed in and visitors enter the room, Golia will attend to other things, so he says. So for the weeks to come art production happens this way — without the artist being present… Nothing can stop the viewer from finding a good dose of humour and irony in works positioned like Golia’s — particularly when they also contain a position of critical distance to oneself and to being an artist per se. Instead of celebrating a self-involved cult of genius, Golia instead arranges his position in the wings, presenting generosity as an artistic gesture, as well as exchange and an attempt to sensitize the viewer to what we expect of art and artists… To view this as a precisely arranged gimmick would be to fall far short of his concept. Instead Piero Golia seems to be maintaining an overview of his work, even when many parts of it seem, time and again, to be physically far from him. Maybe it also enables him to reflect on the correlations and the connections between individual works, to consider his actions and the work as a whole corpus, to add works to it and to take them away. This is not simply a production site. Piero Golia is one of those artists who uncompromisingly advocate an understanding of art that deals with fundamental questions, far away from events and superficiality. He put it this way once, in a 2010 interview: “If everyone tells you not to jump off the roof or you’ll die, you don’t jump because you trust it as if it were truth. Maybe the artist is the one who’s going to tell you that you can jump, and maybe you’re not going to die.”

Text by Ines Goldbach

Excerpt from the publication The Painter

The catalogue was generously supported by the Roldenfund, Anthony Vischer, Adelaide & Peter Sutter de Vries, Gagosian Gallery, Galleria Fonti. The exhibition has been generously supported by the partners of the Kunsthaus Baselland: kulturelles.bl, Migros Kulturprozent, Gemeinde Muttenz, werner sutter AG, prolog.work.

During Piero Golia's exhibition the two solo shows by Itziar Okariz and Markus Amm were also on display at the Kunsthaus Baselland.