Lara Almarcegui

22.5. —

12.7.2015

Selected press coverage

Lara Almarcegui came to prominence in recent years through a number of unusual projects. She became known to a wide international audience particularly thanks to shows such as her presentation at the Venice Biennial in 2013. Its her first institutional presentation in Switzerland.

Many months before the project Excavated Material from Basel, 2015, began in the Kunsthaus Baselland the artist travelled to Basel several times. She roamed the city landscape with a curious gaze, working from a tight circle around the Kunsthaus and moving out through the urban structure, largely on foot, speaking with the authorities and with architects she knew in order to get to know the current municipal and housing projects in the Basel region: the Dreispitz-Areal; Erlenmatt; Rheinhafen; the demolition of the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW) in Muttenz; projects in Pratteln etc. Certain questions accompanied her throughout: what is the current situation as regards building, what is the consistency of the ground?

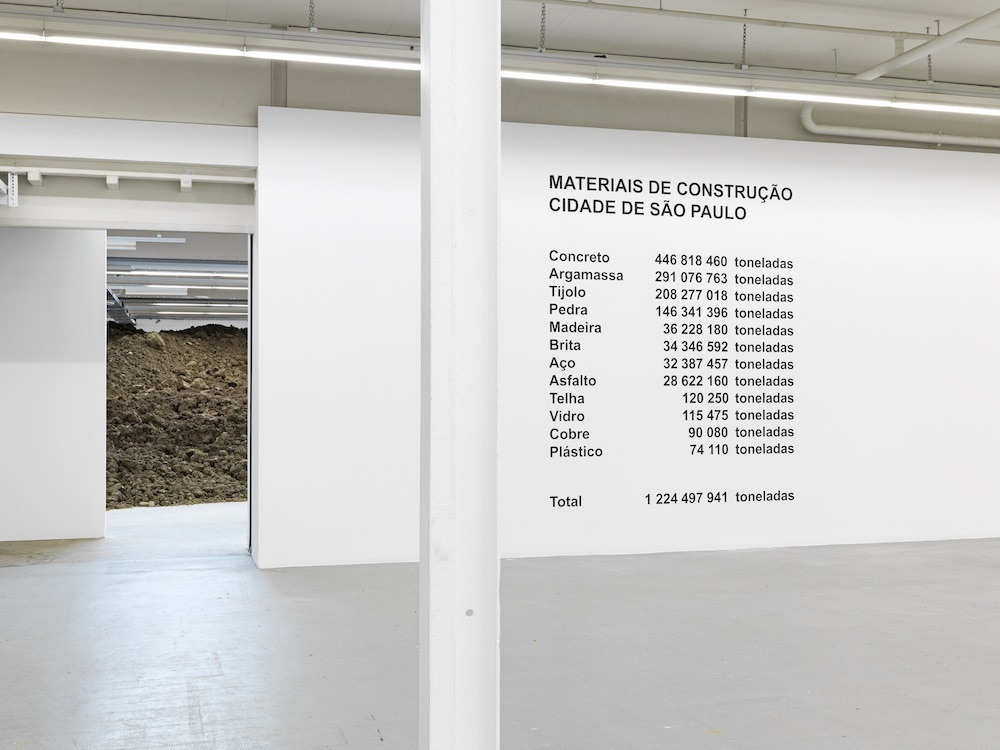

For many years Lara Almarcegui has sounded out the spaces of civilization in our cities and investigated relationships between construction, regeneration and dereliction. She looks at transitional spaces, where the order of the city encounters the order of nature and the new steps in city development emerge. In this time, she has temporarily deconstructed buildings, not to clarify questions of building artistry, architectural theory or cultural history, but to make their materiality and construction visible and tangible. This is particularly clear in Almarcegui’s listing of the building materials of the cities of Dijon, São Paolo and Lund — the millions of tons of concrete, glass, iron, steel or asphalt that hold a city together.

Now, for the Kunshaus Baselland, Almarcegui has piled in 300 cubic metres of excavated material, creating heaps several metres high. This may sound sensationalist. But if you know Lara Almarcegui it is soon clear that it is anything but cheap showmanship. Instead with her works she examines what seems normal and given to us in an informed artistic and scientific manner. What is architecture made of? How is it constructed? Is built space a binding, or also transient, pliable form, which carries its own ruin within, from the moment of construction? What do the countless urban building projects rest upon? Who is in possession; who are the owners? These are the fundamental questions relating to how we live together and coexist in urban contexts that interest the artist.

In her most recent work, Mineral Rights, Tveitvangen, which Lara Almarcegui is showing in the Kunsthaus in the form of a projection, she looks into the essential, yet scarcely asked, questions about ownership of the ground and the depths beneath it. Mineral Rights are regulated differently from country to country and it is customarily impossible for a private individual to acquire them. Lara Almarcegui recently gained mineral rights in Norway, in Tveitvangen, not far from Oslo, for an area of one square kilometre. In the projection that she shows in the Kunsthaus, the viewer is taken into a landscape of information about stone, leftover snow, patches of forest, grass and bushes. It is an area known for the occurrence of iron. Iron is one of the most important materials in the building business; hardly a contemporary building can be made without it. Lara Almarcegui will not excavate the iron, but with her project and the rights that she now holds she draws our gaze to one of the key construction materials and the sometimes remarkable or even questionable nature of how it is held and owned. With her works she does not merely create commentary, but she creates a sensibility of our being, acting and dealing with the world.

Text by Ines Goldbach

«I produce an awareness of how the space we are in is constructed.» Lara Almarcegui & Ines Goldbach. A Conversation

Ines Goldbach (IG): I would like to start with the major project you are planning for your show here in Basel. To describe it briefly: you will bring a huge amount of earth and excavated material from a site in the middle of Basel into the Kunsthaus. There will be around 300 m3 of this altogether. These projects create a lot of questions for any institution, of course, and need any number of partnerships to resolve, for example, how to bring the material into the space, etc.. But from my side this also means that numerous people are involved in the project, people who start to think about it more precisely, who might gain a different perspective regarding the excavated material on the one hand, and on the other hand about art projects in general. Is that something that interests you and how do you evaluate this kind of project within an institution?

Lara Almarcegui (LA): These large projects tend to push a building and its team to their limits, because if a building had to bear all the material of its own construction, the weight would be so great that the building might collapse. The work questions the construction and the institution while also bringing in the past of the building and its future, as a ruin. Surprisingly, the people involved in the installation seem to enjoy that. Although the installation is a heavy job they are inspired by the challenge, which generates a good collaboration.

IG: A good collaboration in what sense?

LA: They share the huge effort required to make it work. They all care about the building and hope to end with a good installation. This effort goes beyond what is usual and demands great cooperation within the team.

IG: You mentioned the word ruin. You are right: every new building has in itself its future of becoming a ruin — material, formless. But every material equally holds the potential to become a certain form: a building; architecture; houses; places; streets; cities; or urban structures. I am thinking about works by you in which you have buried a demolished house, or brought together all the materials required to build a certain building. Is this kind of ‘Gleichzeitigkeit’, the contemporaneousness of past, future and present, something that interests you in your work generally?

LA: The failure of an architectural project is very attractive and this is one of the reasons why we all enjoy ruins. If architecture, by definition, rationalises and closes space, if, when the architect comes, freedom ends, then the ruin, as its failure, is the opposite: the ruin is a promise. The ruin is the same as wasteland; it is a blank suspended in time but it offers possibility. All that architecture cannot give.

IG: This might sound critical in relation to architecture, but I think projects like the one here for Basel also demonstrate how your strategies and your projects have the capacity to heighten sensitivity towards urban planning, architectural projects and the changes and transformation it brings. Is that something that interests you?

LA: My works generate different reactions; they somehow always provoke conversation and discussions on the site’s past and future: why a certain site became empty; who owns it and why it isn’t developed yet; what are the plans? I want to understand how the space around me is constructed and what the processes are that make it as it is. My work is an attempt to better understand where I am and we are in a very specific way…

Extract from the publication Lara Almarcegui

The exhibition and catalogue were generously supported by the Mondriaan Fund, AC/E Spain's Public Agency for Cultural Action, die Hans und Renée Müller-Meylan Stiftung, surrer, Hans Graf Bauunternehmung as well as the supporters of the Kunsthaus Baselland: kulturelles.bl, Basellandschaftliche Kantonalbank, Gemeinde Muttenz, Migros Kulturprozent, werner sutter AG.

During Lara Almarcegui's exhibition the two solo exhibitions by Alexander Gutke and Katharina Hinsberg were also on display.