Cooling Out

Zur Paradoxie des Feminismus

13.8. —

1.10.2006

A cooperation between Kunsthaus Baselland, Muttenz/Basel, Halle für Kunst, Lüneburg and Lewis Glucksman Gallery, University College Cork A project by Sabine Schaschl-Cooper, Bettina Steinbrügge and René Zechlin.

The original goals of the women’s movement, i.e. legal equality, favorable educational perspectives for women, and combating male violence, have been achieved almost everywhere — as opposed to culturally conveyed clichés and traditions passed on from one generation to the next, which are much harder to overcome. But by and large it seems as if the women’s movement has become a victim of its own success and has brought about its own demise, as mostly young women, when being confronted with such issues as equitable participation in education and equal opportunities, don’t actually seem to notice the areas in which they are still substantially disadvantaged. Hence, they often display negative knee-jerk reactions to and a hostile attitude towards mainstream feminism or ‘affirmative action’ and quotas for women, and this simply because they don’t realize that shortcomings still exist and don’t want to be branded as putative victims. For this reason, the term ‘feminism’ has come to be negatively connoted.

Naturally, things are a lot more complex, as illustrated by symptoms such as ‘cooling out’ or by a study conducted by MIT in 1998 which suggests that that “gender discrimination in the 1990s is subtle but pervasive, and stems from unconscious ways of thinking that have been socialized into all of us, men and women alike.” A full-fledged women’s movement pursuing legitimate goals seems to have vanished; what we can see, however, is that women are very much involved in the workings of social mechanisms.

This tends to be the view taken by well-educated single women that belong to the upper middle class — women who are aware that, having almost the same opportunities, they can also shape public and political life provided they are smart and know how to act and hold their own in what is still largely a man’s world. Building women’s confidence and raising their self-esteem, a professed goal of second-generation feminists fighting for recognition, seems to have produced tangible results. According to Peggy Phelan, feminism is based on the conviction that gender constitutes a fundamental category in our social systems. The latter are predicated on hierarchical patterns that normally put men first and women second, giving preference to the male segment of the population in a variety of fields. Even though many demands made by the feminist movement have clearly been met, the cultural image of women still leaves a lot to be desired.

There is a certain backlash regarding the image of women: In a time of crisis in employment markets outdated concepts on the division of labor continue to hold sway, as demands for autonomy and full equality are not given the weight they deserve. To what an extent do our societies, men and women alike, still consider the female body the basis of women’s identity? When talking about the return of sexism, the question arises as to how young female artists deal with these phenomena. After all, critical feminist artists such as Hannah Wilke or Nancy Spero have triggered a “mainstreaming” of sexuality in art.

The exhibition revolves around these questions. It looks into approaches currently taken by young female ‘post-feminist’ artists to this issue, and it explores whether or not ambivalence or rejection of feminism can also be found in them. How is feminism connoted? Are distinctions made between ‘difference-based feminism’ and its constructivist embodiments, i.e. between essentialist interpretations of femininity and discursive-relativistic methodologies that pursue no political or identity-related agenda?

3 Hamburger Frauen, a grouping of female painters comprised of Ergül Cengiz (born in 1975 in Moosburg a.d. Isar, lives in Hamburg), Henrieke Ribbe (born in 1979 in Hannover, lives in Oslo and Berlin), and Kathrin Wolf (born in 1974 in Ruit, lives in Hamburg), executes large-format murals in which they specifically allude to the given exhibition architecture and design. The Paradise City, a quote taken from a song by Guns N’ Roses, is the first part of a three-part mural painting which the artists developed for the exhibition series Cooling Out. As in previous joint projects, each of the three artists works on individually selected motifs and executes them herself. Hence, the work involves three different styles and themes, and it is during preliminary talks that they are fused into a compositional entity. In the wildly proliferating and exuberant universe of their works — the elements of which are gleaned from pictures, architecture, as well as the location of the given exhibition — the artists take turns in playing stereotypical roles as protagonists of their painted worlds. In Kunsthaus Baselland they present themselves in the nude for the first time, facetiously articulating various connotations of femininity and nature. We see a woman mounting a panther and taming the wild beast, a woman whose mirror image questions her existence and the role she is supposed to play, and a woman who playfully appropriates the world of plants as a second skin. These roles may be expanded and modified continuously and serve as a humoristic reminder of the versatility of the female image in today’s world.

In her series of drawings entitled Polly’s Graduation Night Maura Biava (born in 1970 in Reggio Emilia, lives in Amsterdam) traces the life of a young woman who is graduating as a graphic designer. At night she dreams that her life changes completely by meeting other people, by encountering love, by taking decisions relevant to her career, or simply by coincidence and twists of fate. This work illustrates the many different turns a person’s life can take; these changes, however, remain only hypotheses on account of decisions taken or events unfolding in that person’s life. In her entire artistic oeuvre Biava has developed fictitious female personalities that have to adapt to certain socially determined circumstances. Her characters search for their own appropriate identities by playing different roles. Biava’s interest in playing such different roles was aroused when she took part in the performances of Vanessa Beecroft, with whom she took classes at the Milan art academy in the 1990s. Subsequently, Biava devised highly disparate situations in her own work that point in various directions. She also demonstrates the consequences of decisions taken in life. Conducting self-trials, the artist performs as a dancer in Italian TV shows, plays the parts of a housewife, business executive, or mermaid. Her fictitious female alter egos are called Polly, Astrid, Iride, Doride, or Gwen. They pick flowers somewhere in the suburbs, browse through online dating sites, appear in a variety of poses and styles, and allow us to catch a glimpse of the ‘condition postmoderne’. The latter manifests itself as fragmentation, diversity, or the loss of self or depth. Biava’s fictitious characters buck this trend by expressing the problems arising from women’s search for identity in a sensitive and poignant manner.

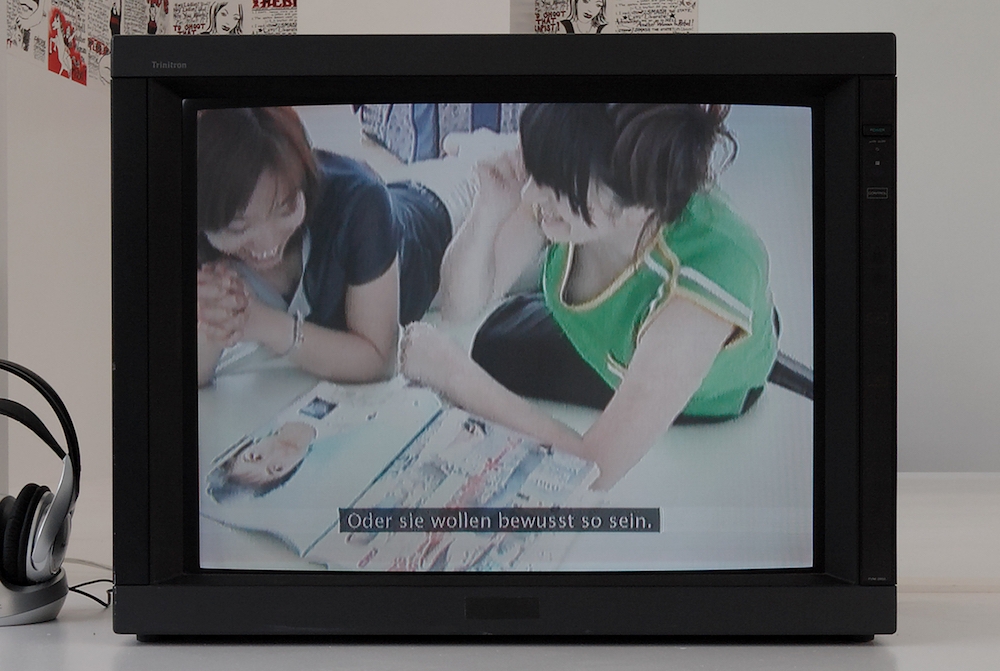

In her video Which one you choose, Esra Ersen (born in 1970 in Ankara, lives in London) challenges the stereotypes associated with role models, as depicted in Japanese magazines avidly read by teenage girls. Together with a group of young women and a fashion critic, the artist analyzes and discusses the images of femininity propagated by the media in today’s Japanese society. There are two opposing clichés she has identified: the ‘cool girl’ and the ‘sweet girlie’. Both modes of presentation are derived from Japanese comic books, and they are ubiquitous to such an extent that there is hardly any room left for other characters. Ersen explores the question of “what it means to relate to a stereotypical character or fantasy characters such as the Mangas, and how these clichés impact a given society.” (Genoveva Rückert)

The series of photographs Here comes Santa by Sylvie Fleury (born in 1961 in Geneva lives in Geneva) is based on a video of the same name. The camera focuses on a pair of slender female feet in dainty high-heels that walk across a red carpet littered with silver Christmas balls crushed by the wearer’s stiletto heels. Gracefully, but with grim resolve, she proceeds with her step-by-step destruction. The fragile red-and-silver Christmas idyll bursts into thousands of little pieces. Fleury, who made a name for herself with her feminist-tinged scrutiny of the fashion world, resorts to ‘male’ symbols and objects quite frequently, whittling away at their smugness by way of surface manipulations.

Dani Gal (born in 1975 in Jerusalem, lives in Berlin) traces the success story of a nine-year old girl, Pricilla Dies, a.k.a. ‘P-Star’, in his video P-Star of 2005. Already at the age of seven, Priscilla debuted as a rap artist in Harlem. In this 30-minute portrait the protagonist recounts her fledgling career, talks about her standing within the rap scene, and also shares some of her rapping talents with the viewer. However, our perception of this young up-and-coming artist is tarnished when we see her father, who has not just raised, shaped, and manipulated her, but is also her music producer. His rather imposing figure casts a shadow over her genuineness, authenticity, and autonomy. This video is the third part of a documentary series devoted to young rap artists.

The joint project Cambio de Lugar_Change of Place_Ortswechsel (2000—2002), promoted by Andrea Geyer (born in 1971in Freiburg, lives in New York) and Sharon Hayes (born in 1970, lives in Los Angeles and New York), initiates dialogs between persons living in Berlin, Mexico, New York, and Vienna. These people can be identified as women with different linguistic backgrounds. The conversations they engage in revolve around current political and social gender-related issues. By way of interviews, this work delves into questions of cultural feminisms, the relations between queer discourse and feminist theory, as well as the struggle for power and interpretative supremacy in politics today. In order to structure these interviews, Geyer and Hayes compiled a list of questions that renders individual points of view comparable. Each interview involves an interviewer, an interviewee, and an interpreter. The video only shows the interpreter who, on account of her presence, symbolizes the constant focus on terminology and interpretation, while alluding to the effect that the concept of translation has on the generation of knowledge and meaning. Information moves permanently between the three participants and is filtered and reinterpreted in an ongoing process. The viewer is therefore not given the opportunity to watch the interviewer or the interviewee, as if obtaining and absorbing information were only possible in the presence of an interpreter. Mechanisms are disclosed that trigger and also define discoursive information. Cambio de Lugar_Change of Place_Ortswechsel takes a critical look at the objectives to be achieved by translation: Who does the talking? Who does the listening? What remains unsaid? What does cultural translation mean? What kind of social group is addressed by a particular language selection? What cannot be translated? Talking and understanding in this world really boils down to a never-ending translation process, both of a linguistic and of a cultural nature. And this fact is actually quite relevant to the communication of gender issues.

Zilla Leutenegger (born in 1968, lives in Zürich) attempts to redesign herself in her works. Her personal moods and thoughts are directly articulated and expressed through the medium of drawings, especially video drawings that have become her trademark. Zilla Leutenegger’s works are snapshots and fragments of ephemeral conceptual realities that manifest themselves as language through art. In Lessons I learned from Rocky I to Rocky III, for example, the video character Zilla, by pulling on red threads in her sweater, shapes differently sized breasts for herself. This scene makes fun of the concept of ideal beauty espoused by our society, as well as of the way we deal with this concept.

The video Fantasy Me, 2004 by Erik van Lieshout (born in 1968 in Deurne, lives in Rotterdam), placed in an oversized red paper lantern (Please crawl underneath!), tells the tale of van Lieshout staying in China for several months, during which period he taught some Chinese women English and, in return, was coached in kung fu. This video centers on the difficulties surrounding the notion of feminism in a Chinese context, as well as those attendant on the proper pronunciation of the word ‘feminism’ by Chinese native speakers. Scenes depicting Chinese people stumbling over English words are interspersed with fighting scenes or those in which expletives are uttered, creating the impression that any patience with the learner of English is wearing thin. Furthermore, Fantasy Me tells us about the special relationship van Lieshout has with Tessa, a Chinese woman who, according to the artist, should have more effective ‘weapons’ for her self-fulfillment. The survival strategy he imparts to her is “being strong and getting more power”. But she refuses to fight, merely dabbles at it, and falls in love with the artist in the process. “There is something uncomfortable, even abusive, about this fact, but it is at the heart of van Lieshout’s unflinchingly honest film“, says critic Tom Morton and deduces from this: “If Fantasy me has a message, it is that love is not a panacea when it is bound up with the stuff of power. Rather, it is something that wounds both parties, making them monsters or midgets, too much or too little themselves.”

In her installation in Kunsthaus Baselland Katrin Mayer (born in 1974 in Oberstdorf, lives in Hamburg) re-stages motifs gleaned from the art of Niki de Saint-Phalle, 1960s pop culture, especially fashion, and everyday life. Already in the 1950s, de Saint-Phalle devoted her attention to the status of men in society which, according to her, was associated with power, violence, and oppression. She said the following about her shooting sessions in the early 1960s: “In 1961 I shot: Dad, all men, short men, tall men, important men, fat men, men, my brother, society, church, the convent, school, my family, my mother, all men, Dad, myself, men. … A war without victims?” With her shooting paintings de Saint-Phalle embodied a new image of women very early, one which was to gain currency in society only later, in the 1970s. When selecting the material she intends to work with, Katrin Mayer realizes that new life may be breathed into (historic) objects by way of repetition, recontextualization, and memories, thus possibly bringing about shifts in their meaning. Through this meaningful and formal incorporation into other referential systems, Mayer reevaluates a distinctly feminist approach. She expands it into the formal idiom of the 1960s and 1970s and places a collage on a large wall with black-and-white stripes that depicts fashion, models, everyday situations, and a whole lot of pop culture. She traces analogies and connections between various spheres of meaning. She sets out with a formal idiom that comes to include political and historical elements as well. Fashion, in this case, is connoted with an ambiguous social code. The stripes stand for separation, for the status of being an outsider. What comes to mind is that de Saint-Phalle herself started out as a fashion model, having what is today perceived by a whole generation of young women the most glamorous job in the world. And it is exactly this one-dimensional view on women that she came to oppose vehemently later on. In close proximity to the architectural space, Mayer devises scenarios in which logical connections and formal analogies are intertwined. They cast an updated and somewhat detached glance at debates on feminism that are a far cry from de Saint-Phalle’s radicalism.

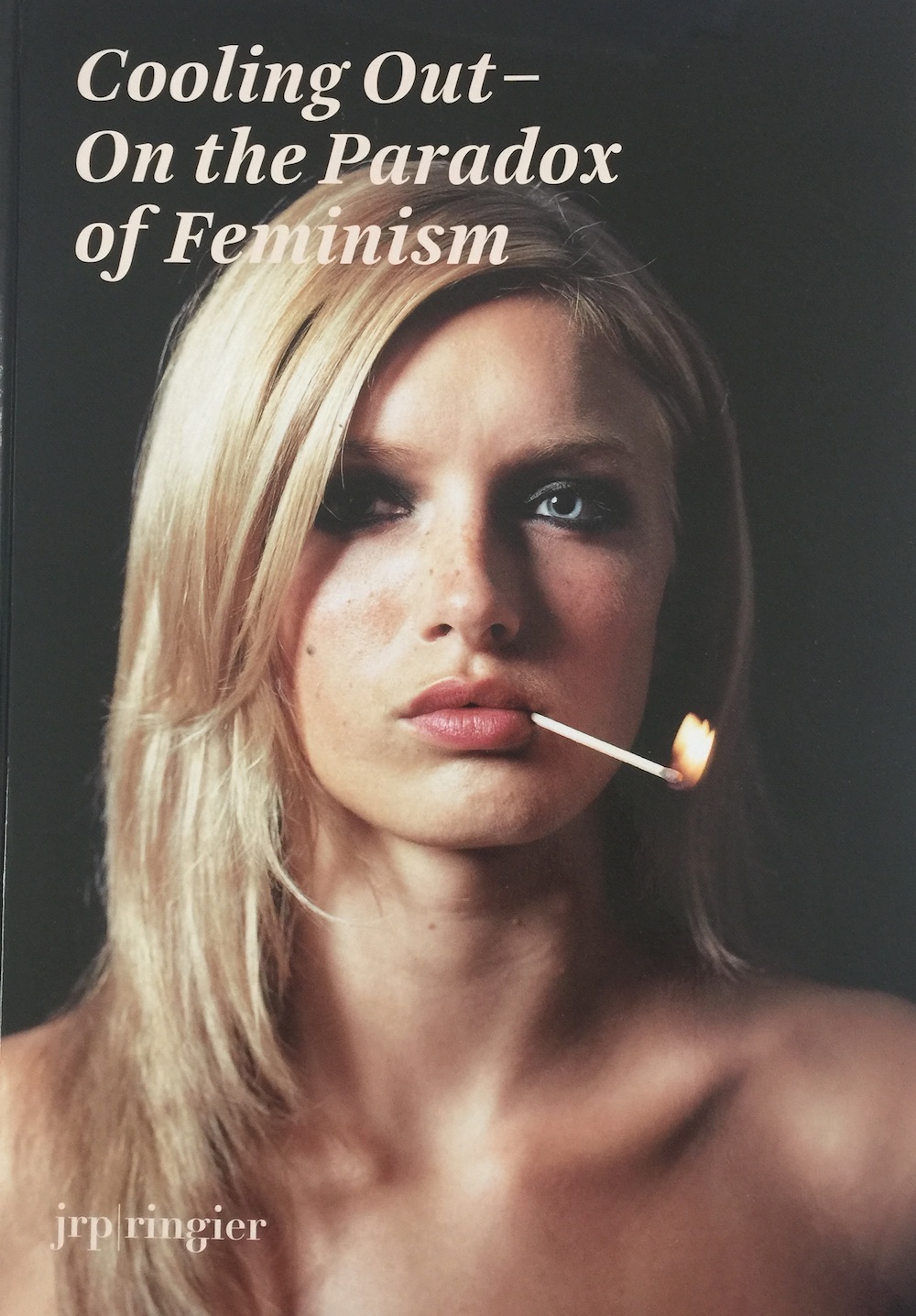

Josephine Meckseper (born in 1965 in Worpswede, lives in New York), editor of Fat Magazine, explores different types of protest with her photographs and installations, as well as their appropriation and neutralization by fashion and everyday culture. A case in point — and recurrent motif — in her works is the Palestinian scarf. A former symbol of identity and solidarity, the scarf became a uniform donned by leftists everywhere, and it has now turned into a fashion accessory. Fashion and lifestyle are neutralized, protest becomes a mere accoutrement. Hence, in Meckseper’s installations, we see photographs showing demonstrations that are placed among the trappings of glamour and lifestyle such as souvenir pictures. In Cooling Out the artist presents a new collection of photographs that convert the situation of feminism into a kind of allegory. Originally a movement with clear-cut goals, feminism has suddenly become a question of perspective. This woman we see in the picture — is she a professional model or does she just pretend to be one? Is the burning match dangling from the mouth a sign of strength or vulnerability? The woman seems convincing, and yet there is this artificiality to her, making what we see appear temporary and fragile.

Renata Poljak (*1974 in Split, lebt in Wien, Split und Nizza) verbindet in ihrem Video Great Expectations, 2005 zwei Feststellungen: Nach Kriegsende entstand in Kroatien eine neue gewalttätige Mentalität, die als sich in Form von Gewalt und skrupelloser Bautätigkeit manifestiert und auf jede Form von Tradition und Respekt gegenüber dem Nachbarn verzichtet. Die zweite Beobachtung zieht eine Verbindung dieser Gewaltgeschichte zur patriachalen Familienstruktur. Die Doku-Fiktion kritisiert letztere anhand des Wunsches des Grossvaters nach einem männlichen Erben, im Film als ‹king› bezeichnet. Die Künstlerin, die gleichzeitig auch die Erzählerin im Film ist, schildert die Familienbeziehungen mit «We know where men stand, and where women must remain». Great Expectations dokumentiert, wie eine patriachale Erziehung, die ständig nach dem «take more, earn more, more, more… It is never enough, especially not for the sons, they are the ones that matter», die sich in einer neue Form der Gewalttätigkeit — in den Zeremonien rund um das Fussballspielen und in architektonischen Umsetzungen — manifestiert.

In her video Je suis une bombe, which is part of the Supernova cycle, Elodie Pong (born in 1966 in Boston, lives in Zürich) presents a young woman wearing a panda bear costume who dances and writhes around a pole, in the manner of striptease performers. At the end of the performance, the young woman takes off her panda head and, holding it in her hand, moves towards the camera. Repeatedly and with a sense of urgency, she says “Je suis une bombe”, as if she needed to convince herself of her own peculiarity. In her videos Pong paints a kaleidoscopic picture of her own generation which she has pegged as narcissistic, searching, and performance-oriented. She remains a bit aloof, but never severs the ties with her protagonists — she knows, after all, that she herself is deeply involved. The body becomes the carrier of communication. This is not surprising as it is mainly the body which shapes our identity today. Pong tries to capture the reality of a generation by juxtaposing the subjective and the objective, as well as the real and the illusionary. The artist runs the entire gamut of contemporary emotions, and underneath some innocuous-looking surfaces she discovers the depths of a silent world drowned out by ambient noise.

Naomi Fisher for the Radical Cheerleaders „Radical Cheerleading is protest and performance! It is activism with pom-poms and combat boots! It is non-violent direct action in the form of street theatre. And it's FUN!” This ‘mission statement’ is found on one of the websites run by the Radical Cheerleaders. But fun is not the only motivation since the topics addressed are sexism, anorexia, sexual abuse, and prevailing concepts of beauty. If cheerleading is the sport taken up by good girls, radical cheerleading is its tongue-in-cheek feisty variant preferred by bad girls. As a member of the American organization www.nycradicalcheerleaders.org, painter Naomi Fisher (born in 1976 in Miami, lives in Miami) — the movement, incidentally, originated in the Sunshine State — presents placards with a feminist content that she has produced in the past few years for her group. In American society, cheerleaders play a crucial role in the process of confirming physical sexuality. More than anything else, cheerleading epitomizes the classical way of bowing to heterosexual demands. Cheerleading transforms girls into ridiculously harmless-looking puppets on a string that perform their exacting athletic duties with rigid discipline, steely determination, and grim smiles, and whose main job is to highlight the performance of the male superstars on the field of play. Rather than subjecting themselves to the beauty standards and physical rigors of conventional cheerleading, Naomi Fisher and her followers transform and radicalize the cute choreographies and sexy outfits. Rather than shouting innocuous words, these cheerleaders sing or chant political slogans or demands. Demonstrations and direct actions seem to be gender-neutral events but in their representation the male element comes to stand for the whole, just like in language. Radical cheerleading focuses on feminine attributes and may therefore interfere with the seemingly ‘neutral’ concept of demonstrations. Radical cheerleading is one way, outside the realm of traditional forms of representation, to make use of creativity and physicality, as required by capitalism, to call into question the construct of sexuality, and to anticipate elements of a joyous rebellion: “Move your ass and your mind will follow!”

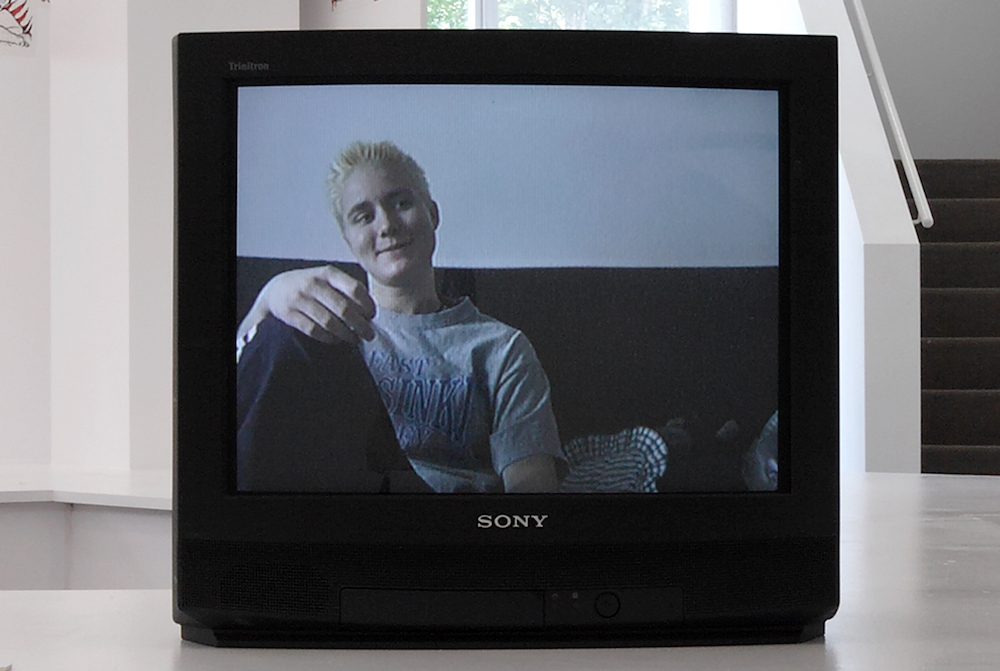

Aurora Reinhard (born in 1975 in Helsinki, lives in Helsinki) articulates the disproportionality of stereotypical gender perceptions, and puts them into perspective by means of her video portrait entitled boygirls, showcasing three young Finnish women who, on account of their androgynous appearance, do not fit easily into conventional gender categories. The protagonists recount their own uncertainties and those people experience when meeting them in everyday life. Each of these three ‘boygirls’ finds her own way of positioning herself in the social and gender spectrum. What also emerges quite clearly is that their identities fall outside the remit of our social male-female dualism. While one of the characters shares with us the problems she faces when she is not recognized as a woman, the other considers the pros and cons of either gender category, as well as the benefits she can derive from her ‘in-between status’. The last protagonist, finally, explicitly talks about the possibility of a sex change.

In her drawings and Japanese picture scrolls, Japanese artist Maki Tamura (born in 1973, lives in Seattle) merges contemporary elements with traditional European and Japanese printing techniques, South-East Asian painting, and illustrations from children’s books from the 19th and 20th centuries. This blend is a reflection of her personal story: born in Japan, raised in Jakarta, and living in Seattle. Tamura has spent most of her life outside her home country and condenses highly diverse impressions into a whole. The installation on display at Kunsthaus Baselland consists of traditional Japanese lanterns as well as a video entitled From a Distant Land (2001), in which an unfathomable female character slowly extricates herself from her situation. The background to this: Tamura discovered fragments of an old Cinderella story in Jakarta. In this version, in contrast to the Western fairytale, it is the mother-in-law that emancipates herself and leaves the house to find her happiness elsewhere. She is an active woman and opts for a new life, while the Cinderella character responds passively to whatever events might unfold. This video dissolves stereotypes and clichés, with a view to challenging them and to critically reflecting on one’s own potential and capacity to act.

In this exhibition Pernille Kapper Williams (born in 1973 in Odense, lives in Frankfurt am Main) deals with the pioneers of the cosmetics industry: Helena Rubinstein, Estée Lauder, and Elizabeth Arden. The manner in which these women are assessed in the exhibition context is ambivalent. All three of them set out in the 1930s to make their professional dreams come true. They all became entrepreneurs who, driven by a burning ambition, built up and expanded big corporations, making sure that their names became synonymous with well-known global brands. In this respect, they have acted as role models, emulated by a generation of independent and successful (business) women. While the cosmetics industry booms because it promises glamour and elegance — implying that beauty is an ideal that everyone can attain provided the right products are used —, women like Lauder, Arden, and Rubinstein also perpetuated an image of women that regards beauty as the key criterion. By taking a conceptual approach, Pernille Kapper Williams confronts materials and documents with each other and thus forms a referential network. The biographies of the three competing female entrepreneurs constitute the core of this network, and it is here that we learn more about the rise of these women to the top, their business success, and the myths in which their cosmetic products are shrouded. The artist’s research also unearthed an FBI document suggesting that Elizabeth Arden aided and abetted Nazi activities in her businesses in the 1940s.

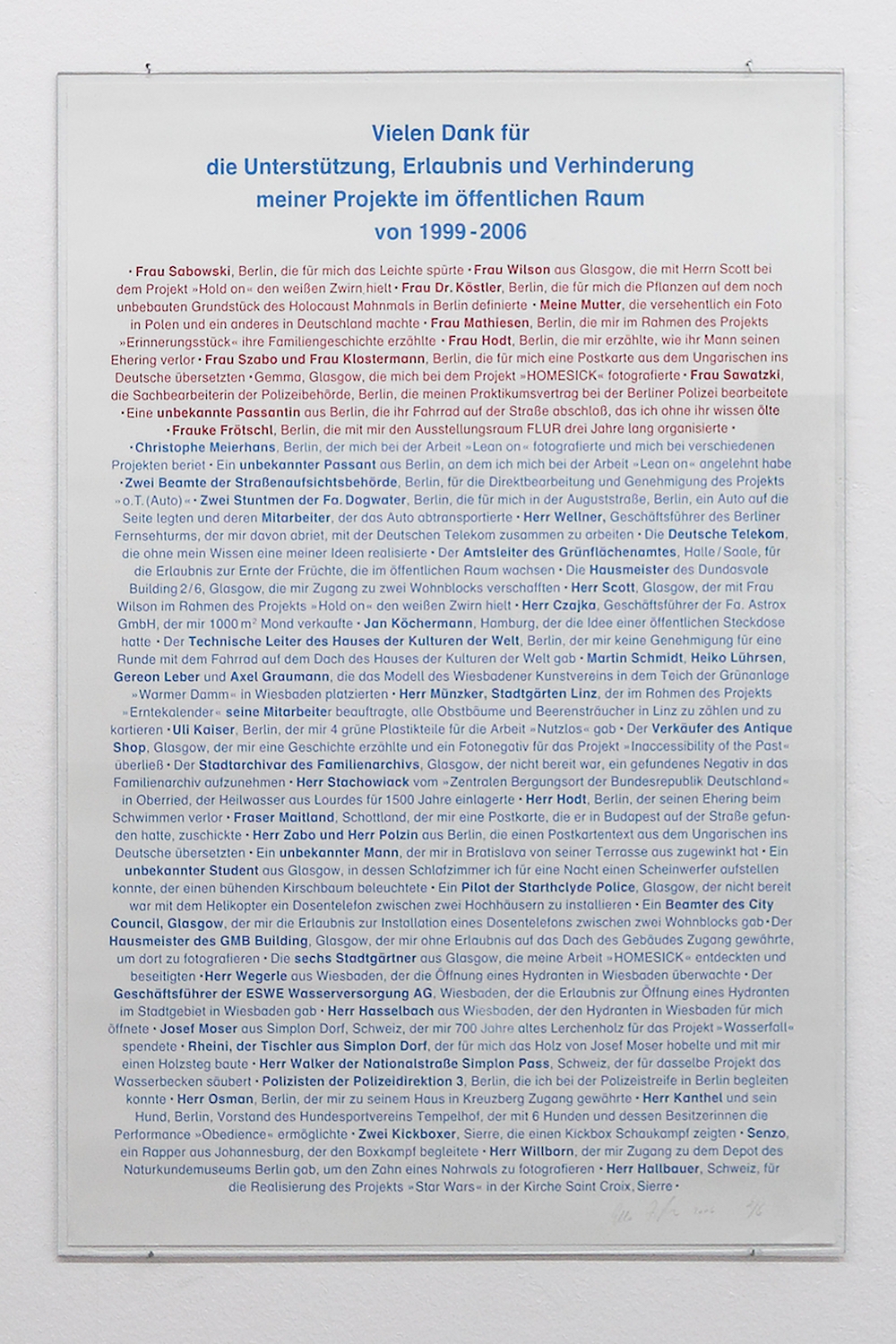

With her work Danksagung (2006), Ella Ziegler (born in 1970 in Ilshofen, lives in Pretoria) takes stock of her oeuvre spanning the period of 1999 to 2006. Realizing that as an artist she had not created any of her works completely autonomously, i.e. without help from outside, she compiled a list with names of all those who had accompanied her during those years. This “nice and very long thank-you list” (Ziegler) begins with women and then continues, almost ad infinitum, with all her male helpers. This somewhat banal practice, which is also an indispensable ritual at any exhibition opening, is suddenly invested with poignancy and discloses, ever so subtly, the extent to which men dominate our social and administrative fabric. Ziegler proceeds meticulously and thanks everybody, even for small and unimportant things. She also expresses her gratitude for failures or permissions that were not given — these situations, after all, often inspire or motivate her in her art. Ziegler takes a conceptual approach and intervenes in everyday life. Her astute observations yield a special portrait of her surroundings. Shocked about the gender inequality in the genesis of her work, she has created a poster in red and blue. For all its simplicity, it is genuinely compelling and expressive.