Rossella Biscotti

The City

20.4. —

16.7.2018

Pressespiegel (Auswahl)

Projektpartner

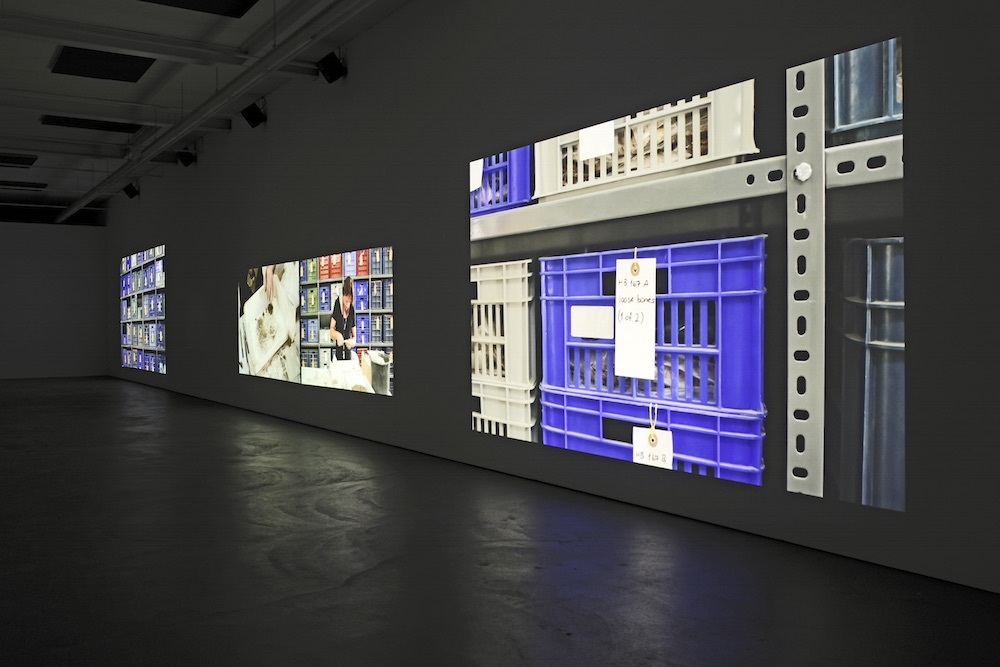

Zu ihrer Einzelausstellung im Kunsthaus Baselland führt Rossella Biscotti erstmals ihre Fünf-Kanal-Videoinstallation The City (2018) vor, die uns einen Einblick in ihre umfassenden Recherche- und Filmarbeiten über die archäologische Ausgrabungsstätte Çatalhöyük im türkischen Konya gewährt. Es ist ihre erste institutionelle Einzelausstellung in der Schweiz.

Rossella Biscotti untersucht in ihrer Arbeit The City die Beziehung zwischen der neolithischen Bevölkerung, die das früheste bis dato bekannte Stadtzentrum der Welt errichtete, und der archäologischen Gemeinschaft, die es im Lauf der vergangenen 25 Jahre zu Tage gefördert hat. Für die Künstlerin ist dies die erste Einzelausstellung in der Schweiz.

Bietet uns das Studium antiker Objekte und Kulturen einen Spiegel, in dem wir die subjektiven Werte der Forscher in ihrer eigenen Gesellschaft betrachten können? Biscotti arbeitete eng mit Ian Hodder, Professor für Sozialanthropologie an der Stanford Universität und Leiter des Forschungsprojekts Çatalhöyük, und seinem internationalen Team zusammen. Sie filmte während der Ausgrabungskampagnen in den Jahren 2015 und 2016. Hodder, einer der Vordenker der postprozessualen Archäologie, hatte seine Ideen schon seit 1993 in Çatalhöyük ausgetestet. Dazu zählten dezentralisierte Projektmanagementteams, selbstreflexives und tagebuchartiges Berichten, gemeinsame Autorschaft, das Teilen von Daten und das Betrachten der Ausgrabungsstätte als lebendige Gemeinschaft, die Fachleute und Ortansässige zusammenbringt. Vor Ort hielt Biscotti fest, wie diese Methoden zur Erforschung eines antiken Volkes um- und eingesetzt wurden, dessen eigene Gemeinschaft diverse radikale sozioökonomische Veränderungen erfahren hatte.

Das über einen Zeitraum von annähernd 2.000 Jahren (ca. 7.500—5.700 v. Chr.) bewohnte Çatalhöyük lässt 18 verschiedene Schichten der Besetzung erkennen und beherbergte einst eine ‹Proto-Stadt› mit fast 10.000 Einwohnern. Angelegt war diese in einem wabenförmigen, labyrinthartigen Gefüge mit gemeinsam genutzten Gebäuden, die sowohl aus- als auch aufeinander gewachsen waren. Der Film beschäftigt sich insbesondere mit diesen urbanen Formen, in denen das Öffentliche und Private relativ fliessend ineinander übergingen, aber auch mit den komplexen Bestattungsritualen, bei denen die Toten inmitten der Lebenden begraben wurden. Darüber hinaus beleuchtet die Künstlerin Indizien der Arbeitsteilung: Was wo und von wem an diesem Ort produziert wurde, legt eine Gesellschaft mit einer geringen bis inexistenten Schichtung nach gesellschaftlichem Status und Geschlecht nahe. Diese organisatorischen Grundsätze, die zeigen, wie eine andere, womöglich freiere Form von Gesellschaft funktioniert haben könnte, werden dem modernen Kontext der Ausgrabungsstätte gegenübergestellt und regen uns zum Nachdenken über die Entwicklung unserer eigenen sozialen Konstrukte an.

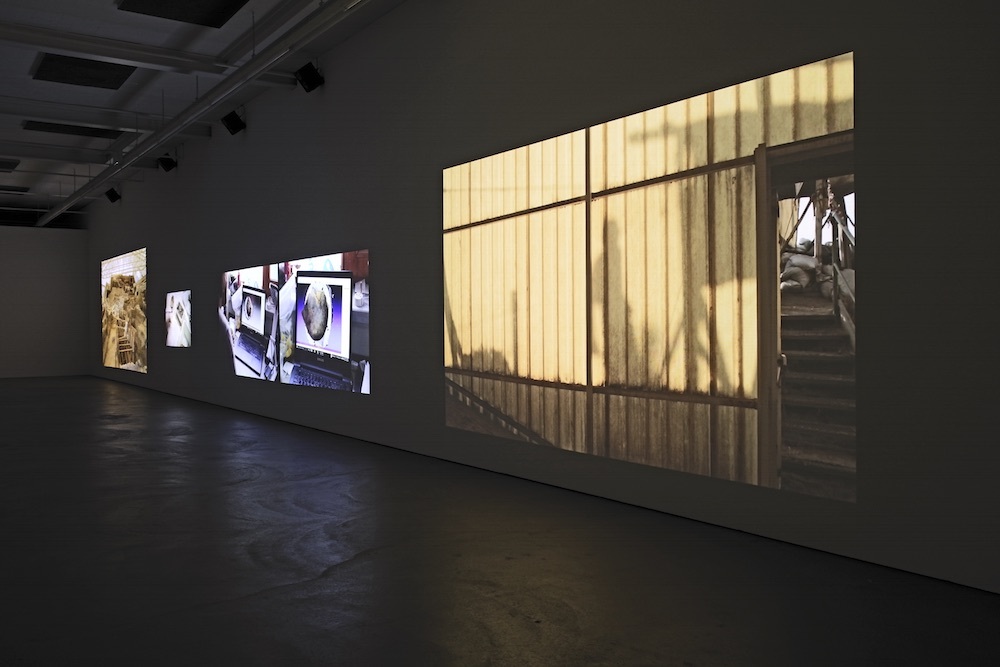

Die Ausgrabungskampagne 2016 fand mit dem Putschversuch in der Türkei ein abruptes Ende und sollte die letzte in Ian Hodders 25 Jahre währendem Projekt sein. Rossella Biscotti hatte zu jenem Zeitpunkt gerade den ersten Tag ihrer Filmarbeiten im zweiten Jahr aufgenommen und stellte ihr Skript nun um. Im Zentrum standen nachfolgend die Bürokratie, die mit der Schliessung der Ausgrabungsstätte einherging, die Meetings, die Abreise des Forscherteams und die leere Landschaft, die schlussendlich zurückblieb.

Rossella Biscotti nutzt eine medienübergreifende Montagetechnik aus Film, Performance und Skulptur, um obskure Momente aus jüngerer Zeit zu erforschen und zu rekonstruieren — häufig vor der Kulisse staatlicher Institutionen. Während sie ihre persönlichen Begegnungen und mündlichen Befragungen zu neuen Geschichten verwebt, hinterlässt auch der Ort ihrer Untersuchungen mitunter seine Spuren an ihren Skulpturen und Installationen. Biscotti hinterfragt die Bedeutung des wiederverwerteten Materials aus einer zeitgenössischen Perspektive und stellt somit eine wahrnehmbare Verbindung zum Jetzt her.

Für die grosszügige Unterstützung der Ausstellung von Rossella Biscotti danken wir dem Mondriaan Fund.

The City wurde in Zusammenarbeit mit Protocinema, Istanbul, produziert.

Parallel zur Ausstellung von Rossella Biscotti fanden jene von Naama Tsabar und Rochelle Feinstein statt.

This weaving is what interested me the most and what I found most relevant to narrate today… Rossella Biscotti in conversation with Ines Goldbach (April 2018)

Ines Goldbach (IG): You are showing your multichannel video installation The City for the first time here at the Kunsthaus Baselland: a project you’ve been working on for some years now. The film contains a series of video notes shot at the Çatalhöyük archeological site during 2015 and professional footage shot during the 2016 excavation season. Archeological sites seem to guarantee that we are able to understand our past and maybe also understand why societies collapse. So it could be helpful for us today looking at our future. What interested you the most about this project, filming this society of archaeologists trying to understand a former society?

Rossella Biscotti (RB): When I first visited the site, I was struck by the architecture: a reversed cityscape with connected spaces that had grown both side by side and on top of each other, horizontally and vertically. My view from the top, and the working of the archeologists in plots below, reminded me of a Tati movie. I had read about the Neolithic revolution, how that civilisation underwent various and radical socio-economic changes, and how Ian Hodder, the project director, had been unveiling the site and his narration also by building up a living community of archaeologists, anthropologists, scientists and local actors who experimented with decentralised project management teams, self-reflective and diarist reporting, co-authorship and data sharing. I looked at them and the way they unearthed the stories; they analysed the data, making hypotheses on how that society radically modified the natural environment domesticating plants and animals, constructing for the first time a way of living together in an interdependent structure that also kept a strong connection with history, with ancestors, thus creating a complex ‘web of relationships’ and time-history. This weaving is what interested me the most and what I found most relevant to narrate today.

IG: So the title The City concentrates not only on the historical, past city of a community leaving there in Neolithic times but also on a contemporary community living and working today?

RB: Yes. The City refers to the proto-city or Neolithic mega-settlement but furthermore to the project of building a society, which happens anytime, anywhere.

IG: Which makes the whole project relevant for the viewer today. I think as well the way you’re presenting it, as a five-channel installation, offers us the chance to feel part of the landscape and part of the moment of excavation.

RB: The five-channel video gives the opportunity to experience the work by walking through the room and choosing your viewing position. In this sense it is like a sculpture. The sound is immersive but at the same time you are watching and listening to fragmented views of a bigger narration. The landscape is the last scene of the work, when, after the attempted military coup d’état, the director decided to call off that year’s excavation, which was also the last of a twenty-five-year project, and to close the site. It had to be my first day of filming according to a movie I scripted which of course didn’t happen. The site closed and I recorded the cleaning up and the bureaucracy, the empty site and the empty landscape. It’s the only time that, as a spectator, you are taken away from the site or labs and have an open view, as it could have been before or after any archeological project, or even before any society. I edited with a sound of a walkie talkie in which two people are taking measurements for the construction of a house (experimental house) to further suggest the idea of the starting of an occupation.

IG: We are mostly used to films and videos with a strong dramaturgy within the narration. Your multichannel film works, as you mentioned, are more like a landscape per se, leading viewers into the space, activating them to move within it, as not all the projections are running at the same time. At the same time the narration is very calm; sometimes you only see people working in peace and sometimes not even people but just the landscape of the archeological site. Plus with a duration of fifty minutes, the film leads you quite deeply into the scenery. What led to your decision about this kind of dramaturgy and narration?

RB: The narration is split in two. In the first part you'll have a feeling of the site at its full collective activity within the excavation, in the labs, as well as the discourse and hypothesis over the ancient civilization. Right at the beginning, while seeing people working side by side, you hear a group discussion where Rosemary Joyce, an American anthropologist and social archaeologist, mentions how society is about community sharing an investment and not about biologically related people: ‘if you think about it from the perspective of all the people who have an investment in the continuity and reproduction of the house, for example, that investment is the proof you belong… your identity with that space is dependent on investment, the fundament of labour’. She continues: ‘for me that particular data is entirely predictable if what we talk about is the notion of society in its very essence, which is collaborative work by a group of people intent on creating and reproducing an estate’. For me this sets the basis of the first part of the narration.

At exactly halfway we see a rotating camera over a few empty Neolithic buildings while hearing and seeing emergency meetings and the decision to pull out. From here on there are no words; the last two burial sites are lifted, the site is swept and prepared for its bureaucratic closure. The images are clearly beautiful, but there is no life. We hear numbers being called, which are the composition of the matrix for the dating, and the film shifts from the manuality to the data collection, composition and sharing. The site will be studied only within its digital form.

At this moment I also thought about all the places which have been destroyed or are inaccessible and only exist now through documentation.

IG: In the last projects you were mainly concentrating on different media like sculpture or installation. This is — beside early projects by you — the first time you are working with only a film installation. Why did you decide to concentrate for this project only on the medium of film?

RB: Since I first visited the site I knew I wanted to work with film. It’s the best medium in which to work on the stratification, the complexity of such a space, its communities and stories.

IG: What interested you the most in the archeological site per se? As far as I know it was one of the first urban cities, with about 3000 inhabitants, and all of a sudden the whole community collapsed. Maybe it’s also interesting that the archeological site was also closed suddenly and brought back to a landscape where it appeared as if nothing had happened.

RB: Yes, it’s not clear why but at the certain point the settlement was abandoned as you mentioned; the population spread some theories saying reaching till Europe. I thought about this when I started seeing the archeologists leaving the site and flying to various destinations in the world. It’s an end and a beginning as the collected experience and knowledge will spread to and change other places.

IG: You were just mentioning Ian Hodder's concept of building up a living community of archaeologists, anthropologists, scientists and local actors who experimented with decentralised project management teams, self-reflective and diarist reporting, co-authorship and data sharing. This is also mirrored within the film. Could this idea of working within a community also be true for a vivid and innovative community in general?

RB: Absolutely. My interest was not in the archeology in itself but in this ideological approach, an incredible experiment of a society on a smaller scale. I find it important to say that all Çatalhöyük archeological data are made available for the world online as creative commons. The idea of community, that starts with that Neolithic ‘web of relationships’, is consciously expanded.