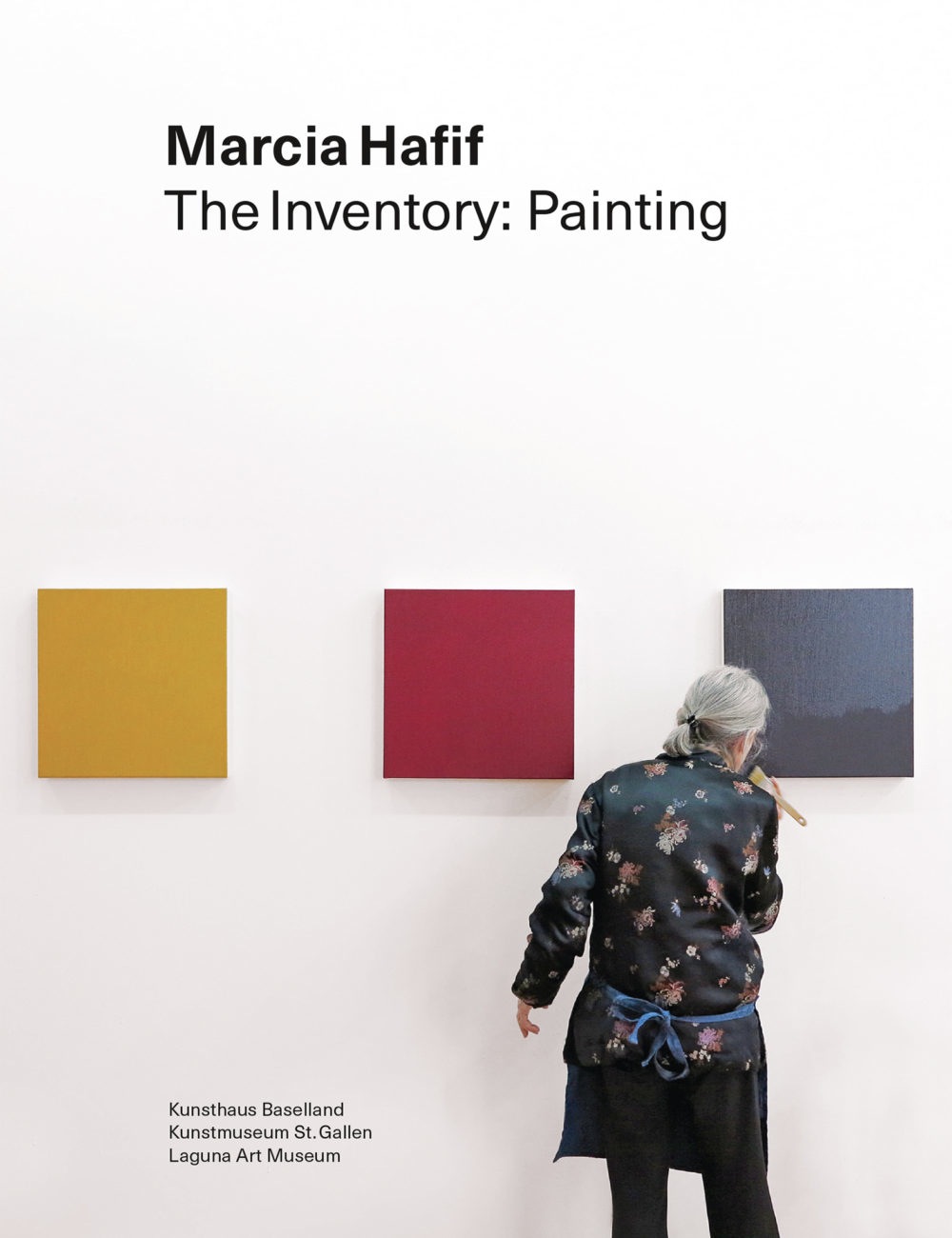

Marcia Hafif

Retrospektive Einzelausstellung

15.9. —

12.11.2017

Zwei Ausstellungen, eine Künstlerin: Um der Ausnahmekünstlerin Marcia Hafif mit ihrem seit bald 70 Jahren gewachsenen Werk gerecht zu werden, schien es sinnfällig, für die Schweiz eine Retrospektive zu konzipieren, die sich über zwei Institutionen erstreckt und das umfassende Œuvre in seiner Fülle und Vielgestaltigkeit optimal zu zeigen im Stande ist. Das Kunsthaus Baselland und das Kunstmuseum St.Gallen haben sich für einmal zusammen getan, um Marcia Hafif eine umfangreiche Retrospektive zu widmen — jedes Haus mit einem eigenen Schwerpunkt. Das Kunsthaus Baselland zeigte u.a. Werke aus den Serien, die vielleicht ihre radikalsten sind: die Black Paintings (1979/80), in denen sie durch das Überlagern von Ultramarinblau und Umbrabraun zu Schwarz gelangte. Weiter wurden erstmals auch Fotografien wie Roman Sundays (1968) und längere Filme wie Notes on Nancy and Bob, India Time oder auch kürzere wie Letters to J-C (Broadway) und Ideal Woman aus dem Jahr 1999.

Schon in den 1970er-Jahren gehörte Hafif zu den Künstlerinnen, deren Verständnis von Malerei früh auf die europäische Kunst einwirkte. 1961 bis 1969 malte sie in Rom, ihrer damaligen Wahlheimat, in der Tradition des amerikanischen Hard Edge Painting. Von Thomas Krens ins renommierte Williams College in Williamstown, MA, eingeladen, versammelte sie 1984 in der namengebenden Ausstellung Radical Painting solidarisch 12 Malerinnen und Maler mit ähnlichen konzeptuellen Ansätzen. «Radical Painting» steht für eine monochrome Malerei, die ohne jeden Abbildcharakter die reine Wirkung von Farbe auf einem Träger untersucht. Auch wenn Marcia Hafif den Begriff für ihr eigenes Schaffen nicht angewendet wissen möchte, geht er ursprünglich doch auf sie zurück.

Die seit den 1960er-Jahren entstandenen eindrücklichen Werkserien erforschten die Möglichkeiten der Farbfeldmalerei grundlegend und erweiterten sie um immer neue Aspekte. Das Unerwartete zu tun war dabei gleichsam Hafifs Markenzeichen. An Extended Grey Scale (1973) mit 106 Gemälden gehört ebenso dazu wie die Serie der berühmten Black Paintings (1979/80) — ihre vielleicht radikalsten Arbeiten —, in denen sie ein tiefes Schwarz durch Überlagern von Ultramarinblau und gebranntem Umbra erzielte. Neuste Werkreihen der Shade Paintings (seit 2013) stehen neben den zweifarbigen, in empirischer Annäherung an den Goldenen Schnitt vertikal unterteilten TGGT (Tomatoes, Grapes and Green Tea; 2006) und der brillanten Farbtransparenz der Glaze Paintings (1995). In den 1970er Jahren begann Marcia Hafif ebenso, die Medien Film und Fotografie parallel zu ihrer Malerei zu nutzen und künstlerisch fortzuentwickeln, etwa in Fotoserien wie Pomona Houses (1971), Roman Sundays (1968) oder auch in Filmen wie Letters to J-C (Broadway) und Ideal Woman aus dem Jahr 1999. Der von ihr festgelegte Begriff The Inventory umfasst ihre grosse Entdeckung der Wirkkraft von Farben, welche sie in Verläufen, Pinselduktus und Linienführung wie in der Entwicklung von Ideen in Serien und Bildfeldern und im Aufgreifen unterschiedlicher Gattungen, darunter Fotografie, Film und Text sowie Malerei und Zeichnung, umsetzte…

Für das Kunsthaus Baselland ist die Präsentation dieser Pionierin des 21. Jahrhunderts etwas Besonderes. Als Ausstellungshalle legt das Haus den Fokus weniger auf die Arbeit mit einer eigenen Sammlung als vielmehr auf die Produktion von neuen Werken mit Künstlerinnen und Künstlern unterschiedlicher Generationen. Mit den Kunstschaffenden werden für den Ort entwickelte Werkpräsentationen in Verbindung mit der bestehenden Architektur realisiert, oder es wird — wie im Fall von Marcia Hafif — eine spezifische Konstellation für die Räume erarbeitet. Im Kunsthaus sind daher erstmals in diesem Umfang Gemälde von Marcia Hafif neben frühen Fotografien, Filmen und Texten zu sehen.

Text von Ines Goldbach und Roland Wäspe

Auszug aus der Publikation Marcia Hafif

Die Ausstellung im Kunsthaus Baselland wurde grosszügig unterstützt durch die Stiftung Roldenfund, Hans und Renée Müller-Meylan Stiftung, Novartis, Embassy of the United States of America sowie den Partnern des Kunsthaus Baselland.

Marcia Hafif in conversation with Ines Goldbach, Laguna Beach, 24/25 July 2017

Ines Goldbach (IG): How did you start taking photographs? There are many early photographs from the 1960s and ‘70s; at that time you were also painting important works like the Black Painting series, for example.

Marcia Haff (MH): What happened is that when I went to Italy in the early 1960s, and in 1961 a friend gave me a camera, just a little camera. I used it to take photos of my paintings but then I had a baby, and once you have a baby you have to photograph the baby! I did that a bit and then we had a friend who lived near Via Barbuino in Rome. He was a famous photographer called Tony Vaccaro. He is not well known in the art world, but he is as a World War II photographer. By the time I knew him in the 1960s he was a photographer for Life magazine and he was sent everywhere to photograph famous people for magazines. I was thinking about photography and Tony said I needed a good camera. He came with me to a photography shop and examined what was there and decided which one I should have. I bought that camera and he showed me how to work with it. It was pretty simple in those days.

IG: So he inspired you to use the camera in a professional way?

MH: Well, what he did was that he gave me the address of the laboratory that printed his photos, and so I got mine printed there too. When they came back, they looked wonderful. I really felt like a photographer. Not all of them were good, but some of them were. So I continued photographing in Rome. A lot of my photos were of my son on the beach or in the city. Then I began photographing other things in Rome that I liked — like windows that interested me. But I left Rome and then taking pictures in New York changed the direction. But I still continued.

IG: Most of your photographs were black and white, even later on, is that right? Compared, for example, with the films where you used colour and the recent photo series which are also in colour.

MH: The early ones were all black and white, yes. They did not become colour until I came to Laguna Beach in 2000, and then I began photographing in colour. These are from an iPhone. It was a gradual transition from black and white photographs using film to colour film and then to colour without film, to digital. This is happen to everything. The longest film that I made is an hour long, Notes on Bob and Nancy. I began when I was a student at the University of California, Irvine, and I had a couple of friends and used them as the subjects of the film. I was shooting black and white still photos, then filming but with no sound. I was using Super 8, and suddenly there could be sound with Super 8, then colour. So this longer film, and the media, developed in tandem.

IG: The photo series Avenida Madera is the only one framed in red. Why is this? You mentioned once that it was a deliberate decision.

MH: When I began to show more photographs, I realised that I did not want to adopt a ‘signature frame’, like all the early black and white photographers using a white background with a black frame. I thought that each series could have an appropriate frame, and for Avenida Madero the colour red came to mind. In the frame shop I had to choose the spacer and the details of the frame, but I liked the narrow, shiny red frame. I have not used it on any other group. For the 4 x 6 inch series Roman Sunday I wanted an inexpensive, easily available frame where I could insert a photo and take it out again because there are so many of them. One thing I do not like about frames is that they need to be damaged to remove the framed work. For Ideal Women, a series of black and white photographs, I used cheap metal frames with a tilting stand in the back that could be placed on a table or desk. Another group in colour, J.C. at La Ciotat, (10 or 12 photos), was installed unframed, each image held up by magnets. The new iPhone photos are mounted on aluminium and spaced from the wall, unframed.

IG: Could you tell me more about the two series Avenida Madero and Roman Sunday? What motivated you to take these pictures?

MH: Avenida Madero (Madero Avenue) in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, was the location of my Aunt Irma's house. I shot the photos visiting there soon after she died; her daughter was showing me around the house. The Roman Sunday photos were shot in 1972, one Sunday in Trastevere, Rome. I set up the camera in the piazza - Santa Maria in Trastevere — and captured each person who came out of the cafe. 70 in all, on 2 rolls of film.

IG: Your short films also remind me of your photographs a great deal, as the camera is often focused on one image, sometimes not moving for minutes at a time, like a still. Instead of a narrative, I think it’s more about looking intensively at a subject. At the same time there is always music in your films. Do you record this while filming?

MH: Yes. I played the music while I was shooting. I turned on the music and filmed.

My camera focussed. In the ‘90s I was in London and at that time I heard about Olivier Messiaen and his music and his interest in the sound of birds. I also liked Erik Satie very much — so one of the films also has music by Satie, when you are watching the Ideal Woman and she looks like she is waiting for someone. This kind of music while she is sitting in a bar waiting, but nobody ever comes; she is left alone.

IG: I think the music is also something that draws the viewer into the film.

MH: Yes, it does. That’s why I used the music.

IG: You just mentioned the film Notes on Nancy and Bob. Your second long-duration film is India Time. How long were you in India to make this film?

MH: I guess it was about two or three weeks. At that time I was living with Robert Morris and he was invited there to do some work. So I also went and began to make some paper works and drawings — and I also had a camera so I took pictures. We went to Kashmir too and I took more pictures there. Afterwards I spend about a year in New York creating the film.

IG: Together with the films, photography and of course painting and drawing, writing has always been an essential part of your work — reviews and texts on exhibitions and painting in general like the essay Getting On with Painting that was published in Art in America in 1981, as well as other essays and texts — some in connection with films, other not. And you’ve also mentioned a longer text you wrote in recent years.

MH: Yes, I have written what I call a book, which is 250 pages that I have never really published but I allowed a few people to read. I call it a book because it isn’t a novel. It’s various narratives and it’s also pretty autobiographical, ranging from descriptions of things that happen and places, to just everyday thoughts, sitting here in my studio thinking about this. Meditations on old age — before I consider myself old [she laughs]. It’s neither a memoir, nor a novel. Most of all, it is a collection, of writings I have done at different periods of my life, often in notebooks, sometimes even in e-mail, which doesn’t always fit together properly. Starting ‘the book’ I realised that I write all the time, or previously I did more than I do now, and what I wrote came in different forms but I could bring them together: they were all coming from the writing part of my mind even when based on different experiences.

IG: Reading your texts and looking at the films, photographs, drawings and paintings I see a parallel artistic attitude. Can you describe why you are interested in writing when you are painting or drawing at the same time?

MH: My writing is sporadic, I write when there is something I really must write about. At times an accumulation of notes adds up to a larger outcome, like when the notes on my painting table made my 1978 article in Artforum, Beginning Again, or even, on the other hand, when a critic made a mistake as to the dimensions of a Ryman painting, and I saw that and it had to be corrected. Or there are certain moments when something very specific happens; it’s always a kind of experiment, like with the paintings where I paint something to see what it looks like: that technique, that mix, that colour that size, etc. They are experiments, but ones focused on an event, something catching my attention, even a plan at times. The video and the films came about in this way too, when my attention is caught, and I want to make a longer film after enjoying smaller, shorter ones, or I’m drawn to the unusual weeds suddenly and unexpectedly appearing in my garden.

IG: I am very curious when I read quotations taken from this book and other texts you’ve published and see them next to your paintings, photographs, films and drawings. I think you’ve only rarely shown all these together, or could it be that you’ve never done so before?

MH: I once included some photographs with paintings in a gallery show. When I showed films, I showed them separately. So yes, it will be interesting to see all of them together, creating something new.

Parallel zur Ausstellung von Marcia Hafif wurde die Einzelausstellung von Maja Rieder gezeigt.